project structure

Structuring a project is not really exciting, nor is it the main focus in a project life, but it’s certainly one of the most important decision to make at the beginning of the project if you do not want to have a massive refactoring afterwards and if you want your project to be quickly understood and workable by other developers.

If you want to directly check the code: Github project

Sample project

To compare the different project structure, we will use a simple pet store project to:

- add new pets

- get a pet

- order a pet

- get an order details

Patterns

Here are some common project structures I used:

Flat project structure

The fastest way to structure a project.

This project structure is quite straightforward: one single project and split the project into abstraction functions by package:

.

└── ...

├── config # app configuration

├── controller # web layer

├── dao # persistence layer interfaces

│ └── impl # persistence layer implementation

├── model # data representations

└── service # business logic layer interfaces

└── impl # business logic layer implementationPattern analysis

Each abstraction is put in their own package and is performing a specific role and responsibility within the application (e.g. data representations or business logic).

It’s an easy way to separate the classes. If we want to add new functionalities, we can add the classes into the corresponding packages.

The package names are quite straightforward and understandable by most developers, as they are named after the “n-tier architecture” pattern’s layers, which is (or was) the de facto standard for most Java EE applications, and therefore they are widely known by most developers.

This flat structure can make a good starting point to quickly start developing new web applications.

Considerations

All classes are in public scope, hence everyone can use everyone, e.g. the controller package

can directly access to the dao classes, which can violate the layer scopes if one is not careful.

In this organisation, one may be lazy and will tend to create a GOD service class that depends on

everyone to perform some complex logic. In other words, this structure does not prevent using

anti-patterns.

This project structure tends to lend itself toward monolithic applications, and it’s really not recommended to continue using this pattern if the application starts to be big. Indeed, because each package can be tightly coupled, it’s difficult to scale the project.

Moreover, it’s really difficult to extract part of the business logic to another component when using this pattern, as classes tends to be tightly coupled.

Layered project structure

Most common architecture pattern

The project structure follows the layered architecture pattern, otherwise known as the n-tier architecture pattern. The project is split in N components that represent a horizontal layer that performs a specific role within the application.

.

├── persistence # persistence layer

│ └── ... #

│ └── persistence # contains the persistence layer interfaces

│ ├── memory # memory implementation of the persistence layer

│ └── model # model / entities of the project (useful for ORM)

├── domain # business layer

│ └── ... #

│ └── domain # contains the business logic interfaces

│ └── simple # simple implementation of the business logic

└── web # web layer

└── ... #

└── web #

├── config # app configuration

├── controller # controllers to manage request inputs

└── dto # Data Transfer Objects used by the controllersPattern analysis

Each abstraction is put in their own package and is performing a specific role and responsibility within the application (e.g. data representations or business logic).

It’s an easy way to separate the classes. If we want to add new functionalities, we can add the classes into the corresponding packages.

The package names are quite straightforward and understandable by most developers, as they are named after the “n-tier architecture” pattern’s layers, which is (or was) the de facto standard for most Java EE applications, and therefore they are widely known by most developers.

Compared to the flat pattern, each layer is isolated and can only be accessible if the component is dependent of one another, thus mitigating some silly mistakes, like having the persistence layer accessible directly from the controllers.

Considerations

The split by abstraction layer is easy and allows grouping common function concerns. However, it’s much too focused on the technical part of the project, especially too focused on the database and the entities, not on the business part of the project. Hence, it brings lots of constraints when dealing with new features, which sometimes leads to twist some functionalities to make it work with this project structure.

There is often a core, utils, or common project in this type of structure because some classes

do not belong to any of the abstraction layer. However, this type of component is often a “garbage”

component, somewhere to put anything.

Like the flat pattern, it’s really difficult to extract part of the business logic to another component when using this pattern, as components tends to be tightly coupled.

Another point is that it’s also tightly coupled to vendors. So as the project grows, it’s quite hard to change the vendor or the framework.

Resources

Modular project structure

Group by business logic.

.

├── app # module regrouping all modules

│ └── ... #

│ └── app #

├── order # order component

│ └── ... #

│ └── order #

│ ├── config # component configuration

│ ├── controller # web layer

│ ├── dao # persistence layer interfaces

│ │ └── impl # persistence layer implementation

│ ├── model # data representations

│ └── service # business logic layer interfaces

│ └── impl # business logic layer implementation

└── pet # pet component

└── ... #

└── pet #

├── config # component configuration

├── controller # web layer

├── dao # persistence layer interfaces

│ └── impl # persistence layer implementation

├── model # data representations

└── service # business logic layer interfaces

└── impl # business logic layer implementationEach business logic has their own component. The content of each component can be independent from each

other. Here, I applied the flat pattern for each component, but we can also apply different pattern.

Pattern analysis

It’s quite straightforward to extract part of the project into a micro-service as each component represents a part of the business logic.

This type of structure can be considered as screaming architecture as we immediately know what the component is all about.

Considerations

Even if this organisation recommends having each component their structure, the external dependencies are still common for all components.

In this example, I used Spring Framework to assemble the components and the app component

uses Spring Boot features to glue the components. Thus, it’s quite tightly coupled to the framework,

which means if we want to switch to another, like VertX, it will be quite painful to do it.

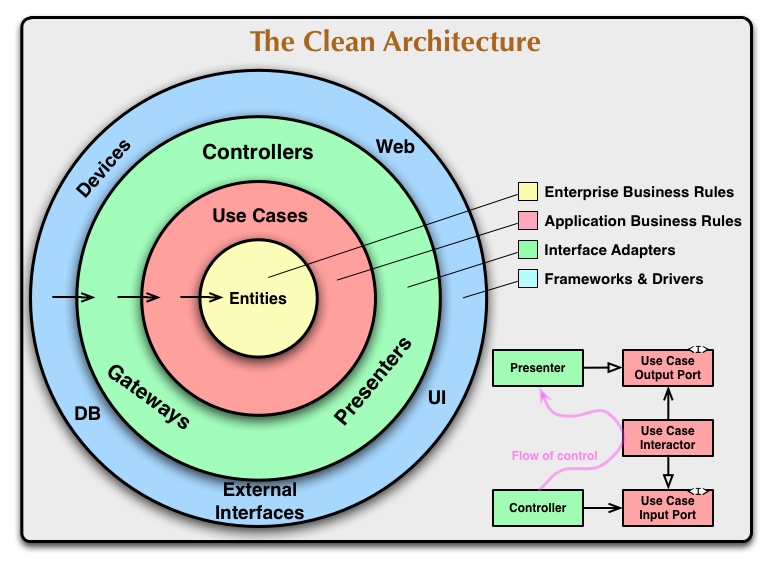

clean architecture pattern

Pattern analysis

The main idea is the separation of concerns and the focus on the use cases. Frameworks and drivers are just detail implementations, thus allowing the developers to defer the decision to pick which database, which framework, etc…

With such organisation, it’s quite easy to switch the database type (e.g. MySQL to PostgreSQL), or

even the framework. As you can see in this sample, the

application/spring-app is completely isolated. The other components do not

depend on the framework. Moreover, with this structure, it’s also easy to package the project to use

it on something else than a webapp, for instance a cron job.

There is lots of benefits of using this organisation. I will not enumerate them as there are already lots of people that already done that. See the resources.

Considerations

This pattern might feel over-engineered, especially for tiny projects.

The code to produce is also way more than other project structures, but it’s still a cost well spent.

For legacy projects, it’s possible to switch to such structure, but it will be hard and painful… Not sure if it’s worth the effort…

Resources

- https://blog.cleancoder.com/uncle-bob/2012/08/13/the-clean-architecture.html

- https://dev.to/pereiren/clean-architecture-series-part-3-2795?signin=true

- https://github.com/carlphilipp/clean-architecture-example

- https://github.com/mattia-battiston/clean-architecture-example

- https://github.com/gshaw-pivotal/spring-hexagonal-example

- https://www.slideshare.net/mattiabattiston/real-life-clean-architecture-61242830

- https://fr.slideshare.net/ThomasPierrain/coder-sans-peur-du-changement-avec-la-meme-pas-mal-hexagonal-architecture