htop

For the longest time I did not know what everything meant in htop.

I thought that load average 1.0 on my two core machine means that the CPU usage is at 50%. That’s not quite right. And also, why does it say 1.0?

I decided to look everything up and document it here.

They also say that the best way to learn something is to try to teach it.

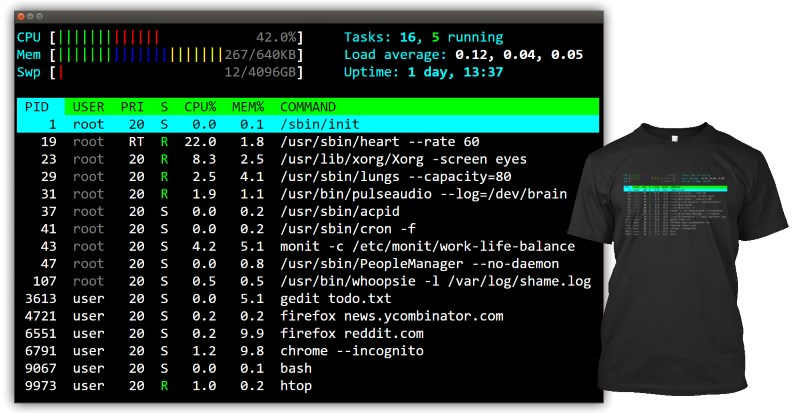

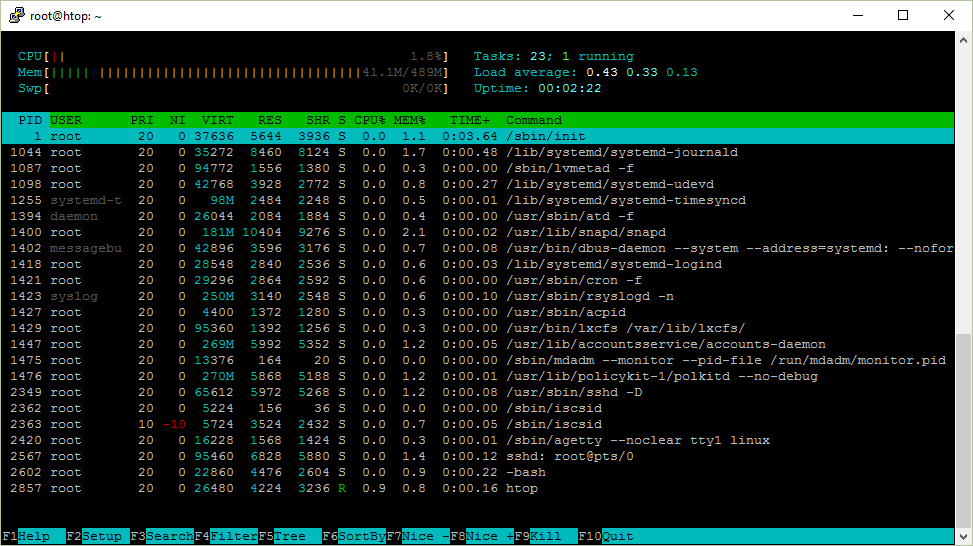

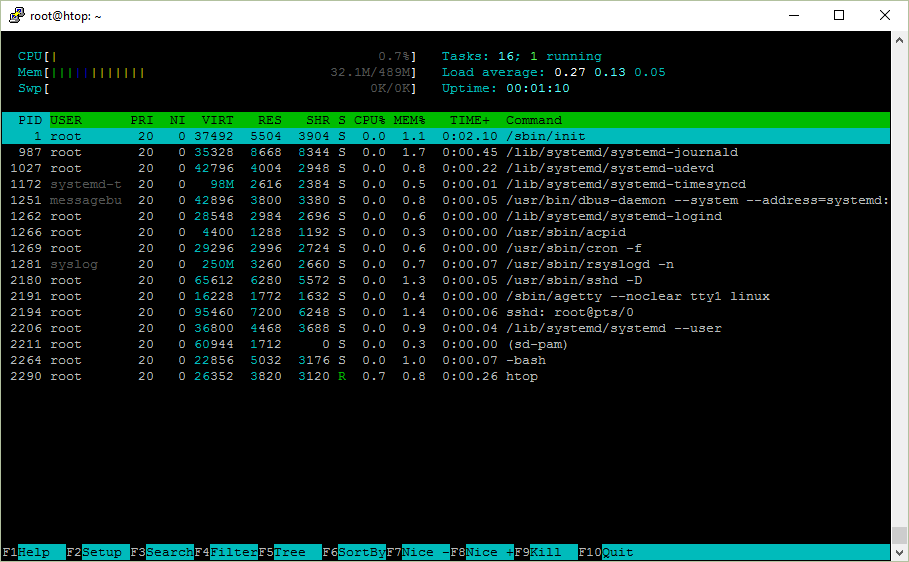

htop on Ubuntu Server 16.04 x64

Here is a screenshot of htop that I am going to describe.

Uptime

Uptime shows how long the system has been running.

You can see the same information by running uptime:

$ uptime

12:17:58 up 111 days, 31 min, 1 user, load average: 0.00, 0.01, 0.05How does the uptime program know that?

It reads the information from the file /proc/uptime.

9592411.58 9566042.33

The first number is the total number of seconds the system has been up. The second number is how much of that time the machine has spent idle, in seconds The second value may be greater than the overall system uptime on systems with multiple cores since it is a sum.

How did I know that? I looked at what files the uptime program opens when it is run. We can use the strace tool to do that.

strace uptimeThere will be a lot of output. We can grep for the open system call. But that will not really work since strace outputs everything to the standard error (stderr) stream. We can redirect the stderr to the standard output (stdout) stream with 2>&1.

Our output is this:

$ strace uptime 2>&1 | grep open

...

open("/proc/uptime", O_RDONLY) = 3

open("/var/run/utmp", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 4

open("/proc/loadavg", O_RDONLY) = 4which contains the file /proc/uptime which I mentioned.

It turns out that you can also use strace -e open uptime and not bother with grepping.

So why do we need the uptime program if we can just read the contents of the file? The uptime output is nicely formatted for humans whereas the number of seconds is more useful for using in your own programs or scripts.

Load average

In addition to uptime, there were also three numbers that represent the load average.

$ uptime

12:59:09 up 32 min, 1 user, load average: 0.00, 0.01, 0.03They are taken from the /proc/loadavg file. If you take another look at the strace output, you’ll see that this file was also opened.

$ cat /proc/loadavg

0.00 0.01 0.03 1/120 1500The first three columns represent the average system load of the last 1, 5, and 15 minute periods. The fourth column shows the number of currently running processes and the total number of processes. The last column displays the last process ID used.

Let’s start with the last number.

Whenever you launch a new process, it is assigned an ID number. Process IDs are usually increasing, unless they’ve been exausted and are being reused. The process ID of 1 belongs to /sbin/init which is started at boot time.

Let’s look at the /proc/loadavg contents again and then launch the sleep command in the background. When it’s launched in the background, its process ID will be shown.

$ cat /proc/loadavg

0.00 0.01 0.03 1/123 1566

$ sleep 10 &

[1] 1567So the 1/123 means that there is one process running or ready to run at this time and there are 123 processed in total.

When you run htop and see just one running process, it means that it is the htop process itself.

If you run sleep 30 and run htop again, you’ll notice that there is still just 1 running process. That’s because sleep is not running, it is sleeping or idling or in other words waiting for something to happen. A running process is a process that is currently running on the physical CPU or waiting its turn to run on the CPU.

If you run cat /dev/urandom > /dev/null which repeatedly generates random bytes and writes them to a special file that is never read from, you will see that there are now two running process.

$ cat /dev/urandom > /dev/null &

[1] 1639

$ cat /proc/loadavg

1.00 0.69 0.35 2/124 1679So there are now two running processes (random number generation and the cat that reads the contents of /proc/loadavg) and you’ll also notice that the load averages have increased.

The load average represents the average system load over a period of time.

The load number is calculated by counting the number of running (currently running or waiting to run) and uninterruptible processes (waiting for disk or network activity). So it’s simply a number of processes.

The load averages are then the average number of those processes during the last 1, 5 and 15 minutes, right?

It turns out it’s not as simple as that.

The load average is the exponentially damped moving average of the load number. From Wikipedia:

Mathematically speaking, all three values always average all the system load since the system started up. They all decay exponentially, but they decay at different speed. Hence, the 1-minute load average will add up 63% of the load from last minute, plus 37% of the load since start up excluding the last minute. Therefore, it’s not technically accurate that the 1-minute load average only includes the last 60 seconds activity (since it still includes 37% activity from the past), but that includes mostly the last minute.

Is that what you expected?

Let’s return to our random number generation.

$ cat /proc/loadavg

1.00 0.69 0.35 2/124 1679While technically not correct, this is how I simplify load averages to make it easier to reason about them.

In this case, the random number generation process is CPU bound, so the load average over the last minute is 1.00 or on average 1 running process.

Since there is only one CPU on my system, the CPU utilization is 100% since my CPU can run only one process at a time.

If I had two cores, my CPU usage would be 50% since my computer can run two processes at the same time. The load average of a computer with 2 cores that has a 100% CPU utilization would be 2.00.

You can see the number of your cores or CPUs in the top left corner of htop or by running nproc.

Because the load number also includes processes in uninterruptible states which don’t have much effect on CPU utilization, it’s not quite correct to infer CPU usage from load averages like I just did. This also explains why you may see high load averages but not much load on the CPU.

But there are tools like mpstat that can show the instantaneous CPU utilization.

$ sudo apt install sysstat -y

$ mpstat 1

Linux 4.4.0-47-generic (hostname) 12/03/2016 _x86_64_ (1 CPU)

10:16:20 PM CPU %usr %nice %sys %iowait %irq %soft %steal %guest %gnice %idle

10:16:21 PM all 0.00 0.00 100.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

10:16:22 PM all 0.00 0.00 100.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

10:16:23 PM all 0.00 0.00 100.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00

# ...

# kill cat /dev/urandom

# ...

10:17:00 PM all 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 100.00

10:17:01 PM all 1.00 0.00 0.00 2.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 97.00

10:17:02 PM all 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 0.00 100.00Why do we use load averages then?

$ curl -s https://raw.githubusercontent.com/torvalds/linux/v4.8/kernel/sched/loadavg.c | head -n 7

/*

* kernel/sched/loadavg.c

*

* This file contains the magic bits required to compute the global loadavg

* figure. Its a silly number but people think its important. We go through

* great pains to make it work on big machines and tickless kernels.

*/Processes

In the top right corner, htop shows the total number of processes and how many of them are running. But it says Tasks not processes. Why?

Another name for a process is a task. The Linux kernel internally refers to processes as tasks. htop uses Tasks instead of Processes probably because it’s shorter and saves some screen space.

You can also see threads in htop. To toggle the visibility of threads, hit Shift+H on your keyboard. If you see Tasks: 23, 10 thr, it means it they are visible.

You can also see kernel threads with Shift+K. When they are visible, it’ll say Tasks: 23, 40 kthr.

Process ID / PID

Every time a new process is started it is assigned an identification number (ID) which is called process ID or PID for short.

If you run a program in the background (&) from bash, you will see the job number in square brackets and the PID.

$ sleep 1000 &

[1] 12503If you missed it, you can use the $! variable in bash that will expand to the last backgrounded process ID.

$ echo $!

12503Process ID is very useful. It can be used to see details about the process and to control it.

procfs is a pseudo file system that lets userland programs to get information from the kernel by reading files. It is usually mounted at /proc/ and to you it looks like a regular directory that you can browse with ls and cd.

All information related to a process is located at /proc/<pid>/.

$ ls /proc/12503

attr coredump_filter fdinfo maps ns personality smaps task

auxv cpuset gid_map mem numa_maps projid_map stack uid_map

cgroup cwd io mountinfo oom_adj root stat wchan

clear_refs environ limits mounts oom_score schedstat statm

cmdline exe loginuid mountstats oom_score_adj sessionid status

comm fd map_files net pagemap setgroups syscallFor example, /proc/<pid>/cmdline will give the command that was used to launch the process.

$ cat /proc/12503/cmdline

sleep1000$Ugh, that’s not right. It turns out that the command is separated by the \0 byte.

$ od -c /proc/12503/cmdline

0000000 s l e e p \0 1 0 0 0 \0

0000013which we can replace with a space or newline

$ tr '\0' '\n' < /proc/12503/cmdline

sleep

1000

$ strings /proc/12503/cmdline

sleep

1000The process directory for a process can contain links! For instance, cwd points to the current working directory and exe is the executed binary.

$ ls -l /proc/12503/{cwd,exe}

lrwxrwxrwx 1 ubuntu ubuntu 0 Jul 6 10:10 /proc/12503/cwd -> /home/ubuntu

lrwxrwxrwx 1 ubuntu ubuntu 0 Jul 6 10:10 /proc/12503/exe -> /bin/sleepSo this is how htop, top, ps and other diagnostic utilities get their information about the details of a process: they read it from /proc/<pid>/<file>.

Process tree

When you launch a new process, the process that launched the new process is called the parent process. The new process is now a child process for the parent process. These relationships form a tree structure.

If you hit F5 in htop, you can see the process hierarchy.

You can also use the f switch with ps

$ ps f

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

12472 pts/0 Ss 0:00 -bash

12684 pts/0 R+ 0:00 \_ ps for pstree

$ pstree -a

init

├─atd

├─cron

├─sshd -D

│ └─sshd

│ └─sshd

│ └─bash

│ └─pstree -a

...If you have ever wondered why you often see bash or sshd as parents of some of your processes, here’s why.

This is what happens when you run, say, date from your bash shell:

bashcreates a new process that is a copy of itself (using aforksystem call)- it will then load the program from the executable file

/bin/dateinto memory (using anexecsystem call) bashas the parent process will wait for its child to exit

So the /sbin/init with an ID of 1 was started at boot, which spawned the SSH daemon sshd. When you connect to the computer, sshd will spawn a process for the session which in turn will launch the bash shell.

I like to use this tree view in htop when I’m also interested in seeing all threads.

Process user

Each process is owned by a user. Users are represented with a numeric ID.

$ sleep 1000 &

[1] 2045

$ grep Uid /proc/2045/status

Uid: 1000 1000 1000 1000You can use the id command to find out the name for this user.

$ id 1000

uid=1000(ubuntu) gid=1000(ubuntu) groups=1000(ubuntu),4(adm)It turns out that id gets this information from the /etc/passwd and /etc/group files.

$ strace -e open id 1000

...

open("/etc/nsswitch.conf", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

open("/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libnss_compat.so.2", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

open("/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libnss_files.so.2", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

open("/etc/passwd", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

open("/etc/group", O_RDONLY|O_CLOEXEC) = 3

...That’s because the Name Service Switch (NSS) configuration file /etc/nsswitch.conf says to use these files to resolve names.

$ head -n 9 /etc/nsswitch.conf

# ...

passwd: compat

group: compat

shadow: compatThe value of compat (Compatibility mode) is the same as files except other special entries are permitted. files means that the database is stored in a file (loaded by libnss_files.so). But you could also store your users in other databases and services or use Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP), for example.

/etc/passwd and /etc/group are plain text files that map numeric IDs to human readable names.

$ cat /etc/passwd

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin

ubuntu:x:1000:1000:Ubuntu:/home/ubuntu:/bin/bash

$ cat /etc/group

root:x:0:

adm:x:4:syslog,ubuntu

ubuntu:x:1000:passwd? But where are the passwords?

They are actually in /etc/shadow.

$ sudo cat /etc/shadow

root:$6$mS9o0QBw$P1ojPSTexV2PQ.Z./rqzYex.k7TJE2nVeIVL0dql/:17126:0:99999:7:::

daemon:*:17109:0:99999:7:::

ubuntu:$6$GIfdqlb/$ms9ZoxfrUq455K6UbmHyOfz7DVf7TWaveyHcp.:17126:0:99999:7:::What’s that gibberish?

$6$is the password hashing algorithm used, in this case it stands forsha512- followed by randomly generated salt to safeguard against rainbow table attacks

- and finally the hash of your password + salt

When you run a program, it will be run as your user. Even if the executable file is not owned by you.

If you’d like to run a program as root or another user, that’s what sudo is for.

$ id

uid=1000(ubuntu) gid=1000(ubuntu) groups=1000(ubuntu),4(adm)

$ sudo id

uid=0(root) gid=0(root) groups=0(root)

$ sudo -u ubuntu id

uid=1000(ubuntu) gid=1000(ubuntu) groups=1000(ubuntu),4(adm)

$ sudo -u daemon id

uid=1(daemon) gid=1(daemon) groups=1(daemon)

But what if you want to log in as another user to launch various commands? Use sudo bash or sudo -u user bash. You’ll be able to use the shell as that user.

If you don’t like being asked for the root password all the time, you can simply disable it by adding your user to the /etc/sudoers file.

Let’s try it:

$ echo "$USER ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL" >> /etc/sudoers

-bash: /etc/sudoers: Permission denied

Right, only root can do it.

$ sudo echo "$USER ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL" >> /etc/sudoers

-bash: /etc/sudoers: Permission denied

WTF?

What happens here is that you are executing the echo command as root but appending the line to the /etc/sudoers file still as your user.

There are usually two ways around it:

echo "$USER ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL" | sudo tee -a /etc/sudoerssudo bash -c "echo '$USER ALL=(ALL) NOPASSWD: ALL' >> /etc/sudoers"

In the first case, tee -a will append its standard input to the file and we execute this command as root.

In the second case, we run bash as root and ask it to execute a command (-c) and the entire command will be executed as root. Note the tricky "/' business here which will dictate when the $USER variable will be expanded.

If you take a look at the /etc/sudoers file you will see that it begins with

$ sudo head -n 3 /etc/sudoers

#

# This file MUST be edited with the 'visudo' command as root.

#

Uh oh.

It’s a helpful warning that says you should edit this file with sudo visudo. It will validate the contents of the file before saving and prevent you from making mistakes. If you don’t use visudo and make a mistake, it may lock you out from sudo. Which means that you won’t be able to correct your mistake!

Let’s say you want to change your password. You can do it with the passwd command. It will, as we saw earlier, save the password to the /etc/shadow file.

This file is sensitive and only writeable by root:

$ ls -l /etc/shadow

-rw-r----- 1 root shadow 1122 Nov 27 18:52 /etc/shadow

So how is it possible that the passwd program which is executed by a regular user can write to a protected file?

I said earlier that when you launch a process, it is owned by you, even if the owner of the executable file is another user.

It turns out that you can change that behavior by changing file permissions. Let’s take a look.

$ ls -l /usr/bin/passwd

-rwsr-xr-x 1 root root 54256 Mar 29 2016 /usr/bin/passwd

Notice the s letter. It was accomplished with sudo chmod u+s /usr/bin/passwd. It means that an executable will be launched as the the owner of the file which is root in this case.

You can find the so called setuid executables with find /bin -user root -perm -u+s.

Note that you can also do the same with group (g+s).

Process state

We are next going to look at the process state column in htop which is denoted simply with the letter S.

Here are the possible values:

R running or runnable (on run queue)

S interruptible sleep (waiting for an event to complete)

D uninterruptible sleep (usually IO)

Z defunct ("zombie") process, terminated but not reaped by its parent

T stopped by job control signal

t stopped by debugger during the tracing

X dead (should never be seen)

I’ve ordered them by how often I see them.

Note that when you run ps, it will also show substates like Ss, R+, Ss+, etc.

$ ps x

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

1688 ? Ss 0:00 /lib/systemd/systemd --user

1689 ? S 0:00 (sd-pam)

1724 ? S 0:01 sshd: vagrant@pts/0

1725 pts/0 Ss 0:00 -bash

2628 pts/0 R+ 0:00 ps x

R - running or runnable (on run queue)

In this state, the process is currently running or on a run queue waiting to run.

What does it mean to run?

When you compile the source code of a program that you’ve written, that machine code is CPU instructions. It is saved to a file that can be executed. When you launch a program, it is loaded into memory and then the CPU executes these instructions.

Basically it means that the CPU is physically executing instructions. Or, in other words, crunching numbers.

S - interruptible sleep (waiting for an event to complete)

This means that the code instructions of this process are not being executed on the CPU. Instead, this process is waiting for something - an event or a condition - to happen. When an event happens, the kernel sets the state to running.

One example is the sleep utily from coreutils. It will sleep for a specific number of seconds (approximately).

$ sleep 1000 &

[1] 10089

$ ps f

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

3514 pts/1 Ss 0:00 -bash

10089 pts/1 S 0:00 \_ sleep 1000

10094 pts/1 R+ 0:00 \_ ps f

So this is interruptible sleep. How can we interrupt it?

By sending a signal.

You can send a signal in htop by hitting F9 and then choosing one of the signals in the menu on the left.

Sending a signal is also known as kill. That’s because kill is a system call that can send a signal to a process. There is a program /bin/kill that can make this system call from userland and the default signal to use is TERM which will ask the process to terminate or in other words try to kill it.

Signal is just a number. Numbers are hard to remember so we give them names. Signal names are usually written in uppercase and may be prefixed with SIG.

Some commonly used signals are INT, KILL, STOP, CONT, HUP.

Let’s interrupt the sleep process by sending the INT aka SIGINT aka 2 aka Terminal interrupt signal.

$ kill -INT 10089

[1]+ Interrupt sleep 1000

This is also what happens When you hit CTRL+C on your keyboard. bash will the send the foreground process the SIGINT signal just like we just did manually.

By the way, in bash, kill is a built-in command, even though there is /bin/kill on most systems. Why? It allows processes to be killed if the limit on processes that you can create is reached.

These commands do the same thing:

kill -INT 10089kill -2 10089/bin/kill -2 10089

Another useful signal to know is SIGKILL aka 9. You may have used it to kill a process that didn’t respond to your frantic CTRL+C keyboard presses.

When you write a program, you can set up signal handlers that are functions that will be called when your process receives a signal. In other words, you can catch the signal and then do something, for example, clean up and shut down gracefully. So sending SIGINT (the user wants to interrupt a process) and SIGTERM (the user wants to terminate the process) does not mean that the process will be terminated.

You may have seen this exception when running Python scripts:

$ python -c 'import sys; sys.stdin.read()'

^C

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<string>", line 1, in <module>

KeyboardInterrupt

You can tell the kernel to forcefully terminate a process and not give it a change to respond by sending the KILL signal:

$ sleep 1000 &

[1] 2658

$ kill -9 2658

[1]+ Killed sleep 1000

D - uninterruptible sleep (usually IO)

Unlike interruptible sleep, you cannot wake up this process with a signal. That is why many people dread seeing this state. You can’t kill such processes because killing means sending SIGKILL signals to processes.

This state is used if the process must wait without interruption or when the event is expected to occur quickly. Like reading to/from a disk. But that should only happen for a fraction of a second.

Here is a nice answer on StackOverflow.

Uninterruptable processes are USUALLY waiting for I/O following a page fault. The process/task cannot be interrupted in this state, because it can’t handle any signals; if it did, another page fault would happen and it would be back where it was.

In other words, this could happen if you are using Network File System (NFS) and it takes a while to read and write from it.

Or in my experience it can also mean that some of the processes are swapping a lot which means you have too little available memory.

Let’s try to get a process to go into uninterruptible sleep.

8.8.8.8 is a public DNS server provided by Google. They do not have an open NFS on there. But that won’t stop us.

$ sudo mount 8.8.8.8:/tmp /tmp &

[1] 12646

$ sudo ps x | grep mount.nfs

12648 pts/1 D 0:00 /sbin/mount.nfs 8.8.8.8:/tmp /tmp -o rw

How to find out what’s causing this? strace!

Let’s strace the command in the output of ps above.

$ sudo strace /sbin/mount.nfs 8.8.8.8:/tmp /tmp -o rw

...

mount("8.8.8.8:/tmp", "/tmp", "nfs", 0, ...

So the mount system call is blocking the process.

If you’re wondering, you can run mount with an intr option to run as interruptible: sudo mount 8.8.8.8:/tmp /tmp -o intr.

Z - defunct (“zombie”) process, terminated but not reaped by its parent

When a process ends via exit and it still has child processes, the child processes become zombie processes.

- If zombie processes exist for a short time, it is perfectly normal

- Zombie processes that exist for a long time may indicate a bug in a program

- Zombie processes don’t consume memory, just a process ID

- You can’t

killa zombie process - You can ask nicely the parent process to reap the zombies (the

SIGCHLDsignal) - You can

killthe zombie’s parent process to get rid of the parent and its zombies

I am going to write some C code to show this.

Here is our program.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

printf("Running\n");

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

printf("I am the child process\n");

printf("The child process is exiting now\n");

exit(0);

} else {

printf("I am the parent process\n");

printf("The parent process is sleeping now\n");

sleep(20);

printf("The parent process is finished\n");

}

return 0;

}

Let’s install the GNU C Compiler (GCC).

sudo apt install -y gcc

Compile it and then run it

gcc zombie.c -o zombie

./zombie

Look at the process tree

$ ps f

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

3514 pts/1 Ss 0:00 -bash

7911 pts/1 S+ 0:00 \_ ./zombie

7912 pts/1 Z+ 0:00 \_ [zombie] <defunct>

1317 pts/0 Ss 0:00 -bash

7913 pts/0 R+ 0:00 \_ ps f

We got our zombie!

When the parent process is done, the zombie is gone.

$ ps f

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

3514 pts/1 Ss+ 0:00 -bash

1317 pts/0 Ss 0:00 -bash

7914 pts/0 R+ 0:00 \_ ps f

If you replaced sleep(20) with while (true) ; then the zombie would be gone right away.

With exit, all of the memory and resources associated with it are deallocated so they can be used by other processes.

Why keep the zombie processes around then?

The parent process has the option to find out its child process exit code (in a signal handler) with the wait system call. If a process is sleeping, then it needs to wait for it to wake up.

Why not simply forcefully wake it up and kill it? For the same reason, you don’t toss your child in the trash when you’re tired of it. Bad things could happen.

T - stopped by job control signal

I have opened two terminal windows and I can look at my user’s processes with ps u.

$ ps u

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

ubuntu 1317 0.0 0.9 21420 4992 pts/0 Ss+ Jun07 0:00 -bash

ubuntu 3514 1.5 1.0 21420 5196 pts/1 Ss 07:28 0:00 -bash

ubuntu 3528 0.0 0.6 36084 3316 pts/1 R+ 07:28 0:00 ps u

I will omit the -bash and ps u processes from the output below.

Now run cat /dev/urandom > /dev/null in one terminal window. Its state is R+ which means that it is running.

$ ps u

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

ubuntu 3540 103 0.1 6168 688 pts/1 R+ 07:29 0:04 cat /dev/urandom

Press CTRL+Z to stop the process.

$ # CTRL+Z

[1]+ Stopped cat /dev/urandom > /dev/null

$ ps aux

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

ubuntu 3540 86.8 0.1 6168 688 pts/1 T 07:29 0:15 cat /dev/urandom

Its state is now T.

Run fg in the first terminal to resume it.

Another way to stop a process like this is to send the STOP signal with kill to the process. To resume the execution of the process, you can use the CONT signal.

t - stopped by debugger during the tracing

First, install the GNU Debugger (gdb)

sudo apt install -y gdb

Run a program that will listen for incoming network connections on port 1234.

$ nc -l 1234 &

[1] 3905

It is sleeping meaning it is waiting for data from the network.

$ ps u

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

ubuntu 3905 0.0 0.1 9184 896 pts/0 S 07:41 0:00 nc -l 1234

Run the debugger and attach it to the process with ID 3905.

sudo gdb -p 3905

You will see that the state is t which means that this process is being traced in the debugger.

$ ps u

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND

ubuntu 3905 0.0 0.1 9184 896 pts/0 t 07:41 0:00 nc -l 1234

Process time

Linux is a multitasking operating system which means that even when you have a single CPU, you can run several processes at the same time. You can connect to your server via SSH and look at the output of htop while your web server is delivering the content of your blog to your readers over the internet.

How is that possible when a single CPU can only execute one instruction at a time?

The answer is time sharing.

One process runs for a bit of time, then it is suspended while the other processes waiting to run take turns running for a while. The bit of time a process runs is called the time slice.

The time slice is usually a few milliseconds so you don’t really notice it that much when your system is not under high load. (It’d be really interesting to find out how long time slices usually are in Linux.)

This should help explain why the load average is the average number of running processes. If you have just one core and the load average is 1.0, the CPU has been utilized at 100%. If the load average is higher than 1.0, it means that the number of processes wanting to run is higher than the CPU can run so you may experience slow downs or delays. If the load is lower than 1.0, it means the CPU is sometimes idleing and not doing anything.

This should also give you a clue why sometimes the running time of a process that’s been running for 10 seconds is higher or lower than exactly 10 seconds.

Process niceness and priority

When you have more tasks to run than the number of available CPU cores, you somehow have to decide which tasks to run next and which ones to keep waiting. This is what the task scheduler is responsible for.

The scheduler in the Linux kernel is reponsible for choosing which process on a run queue to pick next and it depends on the scheduler algorithm used in the kernel.

You can’t generally influence the scheduler but you can let it know which processes are more important to you and the scheduler may take it into account.

Niceness (NI) is user-space priority to processes, ranging from -20 which is the highest priority to 19 which is the lowest priority. It can be confusing but you can think that a nice process yields to a less nice process. So the nicer a process is, the more it yields.

From what I’ve pieced together by reading StackOverflow and other sites, a niceness level increase by 1 should yield a 10% more CPU time to the process.

The priority (PRI) is the kernel-space priority that the Linux kernel is using. Priorities range from 0 to 139 and the range from 0 to 99 is real time and 100 to 139 for users.

You can change the nicesness and the kernel takes it into account but you cannot change the priority.

The relation between the nice value and priority is:

PR = 20 + NI

so the value of PR = 20 + (-20 to +19) is 0 to 39 that maps 100 to 139.

You can set the niceness of a process before launching it.

nice -n niceness program

Change the nicencess when a program is already running with renice.

renice -n niceness -p PID

Here is what the CPU usage colors mean:

- Blue: Low priority threads (nice > 0)

- Green: Normal priority threads

- Red: Kernel threads

http://askubuntu.com/questions/656771/process-niceness-vs-priority

Memory usage - VIRT/RES/SHR/MEM

A process has the illusion of being the only one in memory. This is accomplished by using virtual memory.

A process does not have direct access to the physical memory. Instead, it has its own virtual address space and the kernel translates the virtual memory addresses to physical memory or can map some of it to disk. This is why it can look like processes use more memory than you have installed on your computer.

The point I want to make here is that it is not very straightforward to figure out how much memory a process takes up. Do you also want to count the shared libraries or disk mapped memory? But the kernel provides and htop shows some information that can help you estimate memory usage.

Here is what the memory usage colors mean:

- Green: Used memory

- Blue: Buffers

- Orange: Cache

VIRT/VSZ - Virtual Image

The total amount of virtual memory used by the task. It includes all code, data and shared libraries plus pages that have been swapped out and pages that have been mapped but not used.

VIRT is virtual memory usage. It includes everything, including memory mapped files.

If an application requests 1 GB of memory but uses only 1 MB, then VIRT will report 1 GB. If it mmaps a 1 GB file and never uses it, VIRT will also report 1 GB.

Most of the time, this is not a useful number.

RES/RSS - Resident size

The non-swapped physical memory a task has used.

RES is resident memory usage i.e. what’s currently in the physical memory.

While RES can be a better indicator of how much memory a process is using than VIRT, keep in mind that

- this does not include the swapped out memory

- some of the memory may be shared with other processes

If a process uses 1 GB of memory and it calls fork(), the result of forking will be two processes whose RES is both 1 GB but only 1 GB will actually be used since Linux uses copy-on-write.

SHR - Shared Mem size

The amount of shared memory used by a task. It simply reflects memory that could be potentially shared with other processes.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

printf("Started\n");

sleep(10);

size_t memory = 10 * 1024 * 1024; // 10 MB

char* buffer = malloc(memory);

printf("Allocated 10M\n");

sleep(10);

for (size_t i = 0; i < memory/2; i++)

buffer[i] = 42;

printf("Used 5M\n");

sleep(10);

int pid = fork();

printf("Forked\n");

sleep(10);

if (pid != 0) {

for (size_t i = memory/2; i < memory/2 + memory/5; i++)

buffer[i] = 42;

printf("Child used extra 2M\n");

}

sleep(10);

return 0;

}

fallocate -l 10G

gcc -std=c99 mem.c -o mem

./mem

Process Message VIRT RES SHR

main Started 4200 680 604

main Allocated 10M 14444 680 604

main Used 5M 14444 6168 1116

main Forked 14444 6168 1116

child Forked 14444 5216 0

main Child used extra 2M 8252 1116

child Child used extra 2M 5216 0

TODO: I should finish this.

MEM% - Memory usage

A task’s currently used share of available physical memory.

This is RES divided by the total RAM you have.

If RES is 400M and you have 8 gigabytes of RAM, MEM% will be 400/8192*100 = 4.88%.

Processes

Let’s take a look at the process list in the htop screenshot.

Do you actually need them?

Here are my research notes on the processes that are run at startup on a fresh Digital Ocean droplet with Ubuntu Server 16.04.1 LTS x64.

Before

/sbin/init

The /sbin/init program (also called init) coordinates the rest of the boot process and configures the environment for the user.

When the init command starts, it becomes the parent or grandparent of all of the processes that start up automatically on the system.

Is it systemd?

$ dpkg -S /sbin/init

systemd-sysv: /sbin/init

Yes, it is.

What happens if you kill it?

Nothing.

- https://wiki.ubuntu.com/SystemdForUpstartUsers

- https://www.centos.org/docs/5/html/5.1/Installation_Guide/s2-boot-init-shutdown-init.html

/lib/systemd/systemd-journald

systemd-journald is a system service that collects and stores logging data. It creates and maintains structured, indexed journals based on logging information that is received from a variety of sources.

In other words:

One of the main changes in journald was to replace simple plain text log files with a special file format optimized for log messages. This file format allows system administrators to access relevant messages more efficiently. It also brings some of the power of database-driven centralized logging implementations to individual systems.

You are supposed to use the journalctl command to query log files.

journalctl _COMM=sshdlogs by sshdjournalctl _COMM=sshd -o json-prettylogs by sshd in JSONjournalctl --since "2015-01-10" --until "2015-01-11 03:00"journalctl --since 09:00 --until "1 hour ago"journalctl --since yesterdayjournalctl -blogs since bootjournalctl -fto follow logsjournalctl --disk-usagejournalctl --vacuum-size=1G

Pretty cool.

It looks like it is not possible to remove or disable this service, you can only turn off logging.

- https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd-journald.service.html

- https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/how-to-use-journalctl-to-view-and-manipulate-systemd-logs

- https://www.loggly.com/blog/why-journald/

- https://ask.fedoraproject.org/en/question/63985/how-to-correctly-disable-journald/

/sbin/lvmetad -f

The lvmetad daemon caches LVM metadata, so that LVM commands can read metadata without scanning disks.

Metadata caching can be an advantage because scanning disks is time consuming and may interfere with the normal work of the system and disks.

But what is LVM (Logical Volume Management)?

You can think of LVM as “dynamic partitions”, meaning that you can create/resize/delete LVM “partitions” (they’re called “Logical Volumes” in LVM-speak) from the command line while your Linux system is running: no need to reboot the system to make the kernel aware of the newly-created or resized partitions.

It sounds like you should keep it if you are using LVM.

$ lvscan

$ sudo apt remove lvm2 -y --purge

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man8/lvmetad.8.html

- http://askubuntu.com/questions/3596/what-is-lvm-and-what-is-it-used-for

/lib/systemd/udevd

systemd-udevd listens to kernel uevents. For every event, systemd-udevd executes matching instructions specified in udev rules.

udev is a device manager for the Linux kernel. As the successor of devfsd and hotplug, udev primarily manages device nodes in the /dev directory.

So this service manages /dev.

I am not sure if I need it running on a virtual server.

- https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd-udevd.service.html

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/udev

/lib/systemd/timesyncd

systemd-timesyncd is a system service that may be used to synchronize the local system clock with a remote Network Time Protocol server.

So this replaces ntpd.

$ timedatectl status

Local time: Fri 2016-08-26 11:38:21 UTC

Universal time: Fri 2016-08-26 11:38:21 UTC

RTC time: Fri 2016-08-26 11:38:20

Time zone: Etc/UTC (UTC, +0000)

Network time on: yes

NTP synchronized: yes

RTC in local TZ: no

If we take a look at the open ports on this server:

$ sudo netstat -nlput

Active Internet connections (only servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:22 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 2178/sshd

tcp6 0 0 :::22 :::* LISTEN 2178/sshd

Lovely!

Previously on Ubuntu 14.04 it was

$ sudo apt-get install ntp -y

$ sudo netstat -nlput

Active Internet connections (only servers)

Proto Recv-Q Send-Q Local Address Foreign Address State PID/Program name

tcp 0 0 0.0.0.0:22 0.0.0.0:* LISTEN 1380/sshd

tcp6 0 0 :::22 :::* LISTEN 1380/sshd

udp 0 0 10.19.0.6:123 0.0.0.0:* 2377/ntpd

udp 0 0 139.59.256.256:123 0.0.0.0:* 2377/ntpd

udp 0 0 127.0.0.1:123 0.0.0.0:* 2377/ntpd

udp 0 0 0.0.0.0:123 0.0.0.0:* 2377/ntpd

udp6 0 0 fe80::601:6aff:fxxx:123 :::* 2377/ntpd

udp6 0 0 ::1:123 :::* 2377/ntpd

udp6 0 0 :::123 :::* 2377/ntpd

Ugh.

- https://www.freedesktop.org/software/systemd/man/systemd-timesyncd.service.html

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/systemd-timesyncd

/usr/sbin/atd -f

atd - run jobs queued for later execution. atd runs jobs queued by at.

at and batch read commands from standard input or a specified file which are to be executed at a later time

Unlike cron, which schedules jobs that are repeated periodically, at runs a job at a specific time once.

$ echo "touch /tmp/yolo.txt" | at now + 1 minute

job 1 at Fri Aug 26 10:44:00 2016

$ atq

1 Fri Aug 26 10:44:00 2016 a root

$ sleep 60 && ls /tmp/yolo.txt

/tmp/yolo.txt

I’ve actually never used it until now.

sudo apt remove at -y --purge

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man8/atd.8.html

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man1/at.1.html

- http://askubuntu.com/questions/162439/why-does-ubuntu-server-run-both-cron-and-atd

/usr/lib/snapd/snapd

Snappy Ubuntu Core is a new rendition of Ubuntu with transactional updates - a minimal server image with the same libraries as today’s Ubuntu, but applications are provided through a simpler mechanism.

What?

Developers from multiple Linux distributions and companies today announced collaboration on the “snap” universal Linux package format, enabling a single binary package to work perfectly and securely on any Linux desktop, server, cloud or device.

Apparently it is a simplified deb package and you’re supposted to bundle all dependencies in a single snap that you can distribute.

I’ve never used snappy to deploy or distribute applications on servers.

sudo apt remove snapd -y --purge

- https://developer.ubuntu.com/en/snappy/

- https://insights.ubuntu.com/2016/06/14/universal-snap-packages-launch-on-multiple-linux-distros/

/usr/bin/dbus-daemon

In computing, D-Bus or DBus is an inter-process communication (IPC) and remote procedure call (RPC) mechanism that allows communication between multiple computer programs (that is, processes) concurrently running on the same machine

My understanding is that you need it for desktop environments but on a server to run web apps?

sudo apt remove dbus -y --purge

I wonder what time it is and whether it is being synchronized with NTP?

$ timedatectl status

Failed to create bus connection: No such file or directory

Oops. Should probably keep this.

/lib/systemd/systemd-logind

systemd-logind is a system service that manages user logins.

/usr/sbin/cron -f

cron - daemon to execute scheduled commands (Vixie Cron)

-fStay in foreground mode, don’t daemonize.

You can schedule tasks to run periodically with cron.

Use crontab -e to edit the configuration for your user or on Ubuntu I tend to use the /etc/cron.hourly, /etc/cron.daily, etc. directories.

You can see the log files with

grep cron /var/log/syslogorjournalctl _COMM=cronor evenjournalctl _COMM=cron --since="date" --until="date"

You’ll probably want to keep cron.

But if you don’t, then you should stop and disable the service:

sudo systemctl stop cron

sudo systemctl disable cron

Because otherwise when trying to remove it with apt remove cron it will try to install postfix!

$ sudo apt remove cron

The following packages will be REMOVED:

cron

The following NEW packages will be installed:

anacron bcron bcron-run fgetty libbg1 libbg1-doc postfix runit ssl-cert ucspi-unix

It looks like cron needs a mail transport agent (MTA) to send emails.

$ apt show cron

Package: cron

Version: 3.0pl1-128ubuntu2

...

Suggests: anacron (>= 2.0-1), logrotate, checksecurity, exim4 | postfix | mail-transport-agent

$ apt depends cron

cron

...

Suggests: anacron (>= 2.0-1)

Suggests: logrotate

Suggests: checksecurity

|Suggests: exim4

|Suggests: postfix

Suggests: <mail-transport-agent>

...

exim4-daemon-heavy

postfix

- https://help.ubuntu.com/community/CronHowto

- https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/how-to-use-cron-to-automate-tasks-on-a-vps

- http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/212355/where-is-my-logfile-of-crontab

/usr/sbin/rsyslogd -n

Rsyslogd is a system utility providing support for message logging.

In another words, it’s what populates log files in /var/log/ like /var/log/auth.log for authentication messages like SSH login attempts.

The configuration files are in /etc/rsyslog.d.

You can also configure rsyslogd to send log files to a remote server and implement centralized logging.

You can use the logger command to log messages to /var/log/syslog in background scripts such as those that are run at boot.

#!/bin/bash

logger Starting doing something

# NFS, get IPs, etc.

logger Done doing something

Right, but we already have systemd-journald running. Do we need rsyslogd as well?

Rsyslog and Journal, the two logging applications present on your system, have several distinctive features that make them suitable for specific use cases. In many situations it is useful to combine their capabilities, for example to create structured messages and store them in a file database. A communication interface needed for this cooperation is provided by input and output modules on the side of Rsyslog and by the Journal’s communication socket.

So, maybe? I am going to keep it just in case.

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man8/rsyslogd.8.html

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man1/logger.1.html

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/rsyslog

- https://www.digitalocean.com/community/tutorials/how-to-centralize-logs-with-rsyslog-logstash-and-elasticsearch-on-ubuntu-14-04

- https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-US/Red_Hat_Enterprise_Linux/7/html/System_Administrators_Guide/s1-interaction_of_rsyslog_and_journal.html

/usr/sbin/acpid

acpid - Advanced Configuration and Power Interface event daemon

acpid is designed to notify user-space programs of ACPI events. acpid should be started during the system boot, and will run as a background process, by default.

In computing, the Advanced Configuration and Power Interface (ACPI) specification provides an open standard that operating systems can use to perform discovery and configuration of computer hardware components, to perform power management by, for example, putting unused components to sleep, and to do status monitoring.

But I’m on a virtual server that I don’t intend to suspend/resume.

I am going to remove it for fun and see what happens.

sudo apt remove acpid -y --purge

I was able to successfully reboot the droplet but after halt Digital Ocean thought it was still on so I had to Power Off using the web interface.

So I should probably keep this.

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man8/acpid.8.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Advanced_Configuration_and_Power_Interface

/usr/bin/lxcfs /var/lib/lxcfs/

Lxcfs is a fuse filesystem mainly designed for use by lxc containers. On a Ubuntu 15.04 system, it will be used by default to provide two things: first, a virtualized view of some /proc files; and secondly, filtered access to the host’s cgroup filesystems.

In summary, on a 15.04 host, you can now create a container the usual way, lxc-create … The resulting container will have “correct” results for uptime, top, etc.

It’s basically a userspace workaround to changes which were deemed unreasonable to do in the kernel. It makes containers feel much more like separate systems than they would without it.

Not using LXC containers? You can remove it with

sudo apt remove lxcfs -y --purge

- https://insights.ubuntu.com/2015/03/02/introducing-lxcfs/

- https://www.stgraber.org/2016/03/31/lxcfs-2-0-has-been-released/

/usr/lib/accountservice/accounts-daemon

The AccountsService package provides a set of D-Bus interfaces for querying and manipulating user account information and an implementation of these interfaces based on the usermod(8), useradd(8) and userdel(8) commands.

When I removed DBus it broke timedatectl, I wonder what removing this service will break.

sudo apt remove accountsservice -y --purge

Time will tell.

/sbin/mdadm

mdadm is a Linux utility used to manage and monitor software RAID devices.

The name is derived from the md (multiple device) device nodes it administers or manages, and it replaced a previous utility mdctl. The original name was “Mirror Disk”, but was changed as the functionality increased.

RAID is a method of using multiple hard drives to act as one. There are two purposes of RAID: 1) Expand drive capacity: RAID 0. If you have 2 x 500 GB HDD then total space become 1 TB. 2) Prevent data loss in case of drive failure: For example RAID 1, RAID 5, RAID 6, and RAID 10.

You can remove it with

sudo apt remove mdadm -y --purge

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mdadm

- https://help.ubuntu.com/community/Installation/SoftwareRAID

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man8/mdadm.8.html

/usr/lib/policykit-1/polkitd --no-debug

polkitd — PolicyKit daemon

polkit - Authorization Framework

My understanding is that this is like fine-grained sudo. You can allow non privilegded users to do certain actions as root. For instance, reboot your computer when you’re running Linux on a desktop computer.

But I’m running a server. You can remove it with

sudo apt remove policykit-1 -y --purge

Still wondering if this breaks something.

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man8/polkitd.8.html

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man8/polkit.8.html

- http://www.admin-magazine.com/Articles/Assigning-Privileges-with-sudo-and-PolicyKit

- https://wiki.archlinux.org/index.php/Polkit#Configuration

/usr/sbin/sshd -D

sshd (OpenSSH Daemon) is the daemon program for ssh.

-D When this option is specified, sshd will not detach and does not become a daemon. This allows easy monitoring of sshd.

/sbin/iscsid

iscsid is the daemon (system service) that runs in the background, acting on iSCSI configuration, and managing the connections. From its manpage:

The iscsid implements the control path of iSCSI protocol, plus some management facilities. For example, the daemon could be configured to automatically re-start discovery at startup, based on the contents of persistent iSCSI database.

http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/216239/iscsi-vs-iscsid-services

I had never heard of iSCSI:

In computing, iSCSI (Listeni/aɪˈskʌzi/ eye-skuz-ee) is an acronym for Internet Small Computer Systems Interface, an Internet Protocol (IP)-based storage networking standard for linking data storage facilities.

By carrying SCSI commands over IP networks, iSCSI is used to facilitate data transfers over intranets and to manage storage over long distances. iSCSI can be used to transmit data over local area networks (LANs), wide area networks (WANs), or the Internet and can enable location-independent data storage and retrieval.

The protocol allows clients (called initiators) to send SCSI commands (CDBs) to SCSI storage devices (targets) on remote servers. It is a storage area network (SAN) protocol, allowing organizations to consolidate storage into data center storage arrays while providing hosts (such as database and web servers) with the illusion of locally attached disks.

You can remove it with

sudo apt remove open-iscsi -y --purge

/sbin/agetty --noclear tty1 linux

agetty - alternative Linux getty

getty, short for “get tty”, is a Unix program running on a host computer that manages physical or virtual terminals (TTYs). When it detects a connection, it prompts for a username and runs the ‘login’ program to authenticate the user.

Originally, on traditional Unix systems, getty handled connections to serial terminals (often Teletype machines) connected to a host computer. The tty part of the name stands for Teletype, but has come to mean any type of text terminal.

This allows you to log in when you are physically at the server. In Digital Ocean, you can click on Console in the droplet details and you will be able to interact with this terminal in your browser (it’s a VNC connection I think).

In the old days, you’d see a bunch of ttys started a system boot (configured in /etc/inittab), but nowadays they are spun up on demand by systemd.

For fun, I removed this configuration file that launches and generates agetty:

sudo rm /etc/systemd/system/getty.target.wants/getty@tty1.service

sudo rm /lib/systemd/system/getty@.service

When I rebooted the server, I could still connect to it via SSH but I was no longer able to log in from the Digital Ocean web console.

- http://manpages.ubuntu.com/manpages/xenial/man8/getty.8.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Getty_(Unix)

- http://0pointer.de/blog/projects/serial-console.html

- http://unix.stackexchange.com/questions/56531/how-to-get-fewer-ttys-with-systemd

sshd: root@pts/0 & -bash & htop

sshd: root@pts/0 means that there has been an SSH session established for the user root at the #0 pseudoterminal (pts). A pseudoterminal emulates a real text terminal.

bash is the shell that I am using.

Why is there a dash at the beginning? Reddit user hirnbrot helpfully explained it:

There’s a dash at the beginning because launching it as “-bash” will make it a login shell. A login shell is one whose first character of argument zero is a -, or one started with the —login option. This will then cause it to read a different set of configuration files.

htop is an interactive process viewer tool that is running in the screenshot.

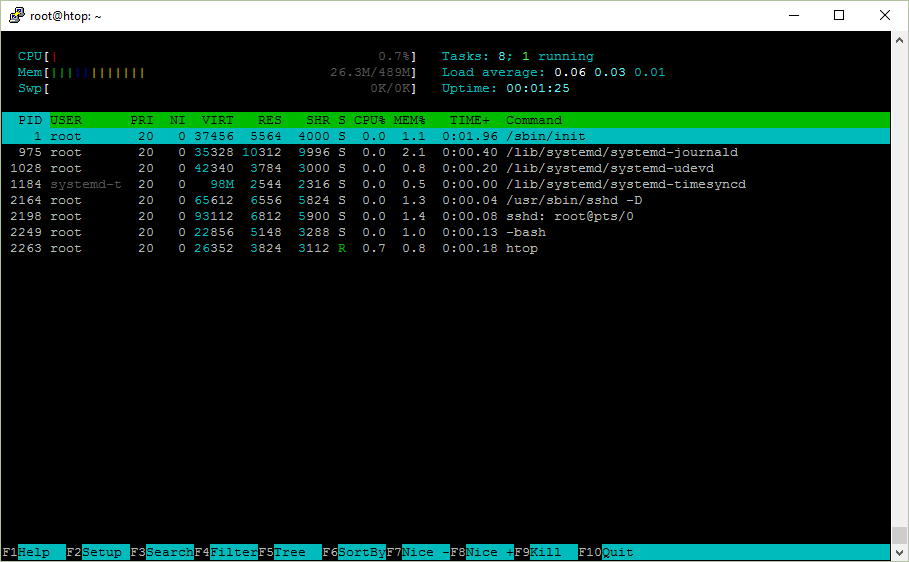

After

sudo apt remove lvm2 -y --purge

sudo apt remove at -y --purge

sudo apt remove snapd -y --purge

sudo apt remove lxcfs -y --purge

sudo apt remove mdadm -y --purge

sudo apt remove open-iscsi -y --purge

sudo apt remove accountsservice -y --purge

sudo apt remove policykit-1 -y --purge

Extreme edition:

sudo apt remove dbus -y --purge

sudo apt remove rsyslog -y --purge

sudo apt remove acpid -y --purge

sudo systemctl stop cron && sudo systemctl disable cron

sudo rm /etc/systemd/system/getty.target.wants/getty@tty1.service

sudo rm /lib/systemd/system/getty@.service

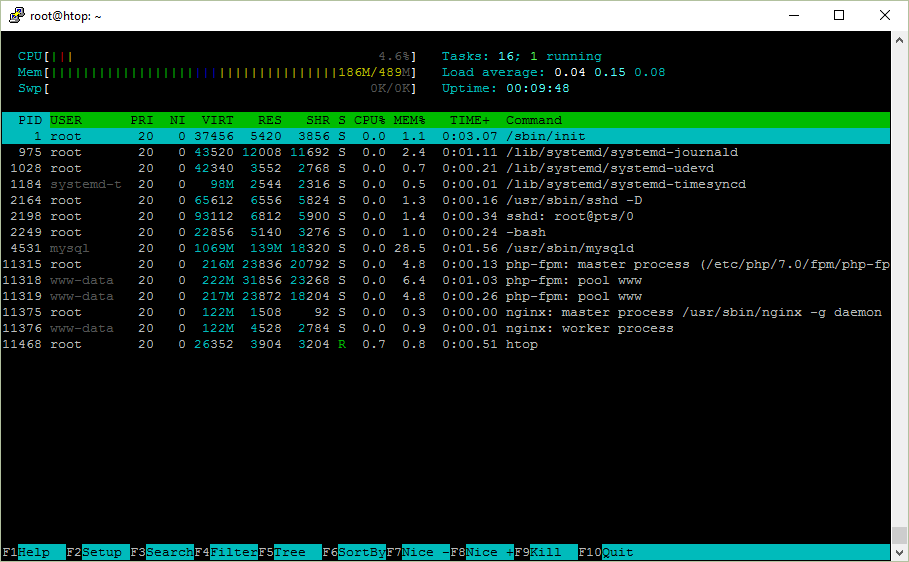

I followed the instructions in my blog post about unattended installation of WordPress on Ubuntu Server and it works.

Here’s nginx, PHP7 and MySQL.

Appendix

Source code

Sometimes looking at strace is not enough.

Another way to figure out what a program does is to look at its source code.

First, I need to find out where to start looking.

$ which uptime

/usr/bin/uptime

$ dpkg -S /usr/bin/uptime

procps: /usr/bin/uptime

Here we find out that uptime is actually located at /usr/bin/uptime and that on Ubuntu it is part of the procps package.

You can then go to packages.ubuntu.com and search for the package there.

Here is the page for procps: http://packages.ubuntu.com/source/xenial/procps

If you scroll to the bottom of the page, you’ll see links to the source code repositories:

- Debian Package Source Repository git://git.debian.org/collab-maint/procps.git

- Debian Package Source Repository (Browsable) https://anonscm.debian.org/cgit/collab-maint/procps.git/

File descriptors and redirection

When you want to redirect standard error (stderr) to standard output (stdout), is it 2&>1 or 2>&1?

You can memorize where the ampersand & goes by knowing that echo something > file will write something to the file file. It’s the same as echo something 1> file. Now, echo something 2> file will write the stderr output to file.

If you write echo something 2>1, it means that you redirect stderr to a file with the name 1. Add spaces to make it more clear: echo something 2> 1.

If you add & before 1, it means that 1 is not a filename but the stream ID. So it’s echo something 2>&1.

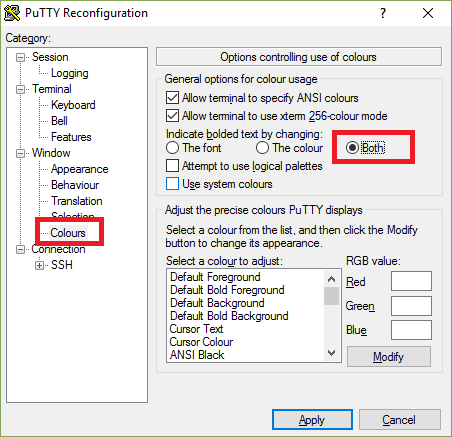

Colors in PuTTY

If you have missing elements in htop when you are using PuTTY, here is how to solve it.

- Right click on the title bar

- Click Change settings…

- Go to Window → Colours

- Select the Both radio button

- Click Apply

Shell in C

Let’s write a very simple shell in C that demonstrates the use of fork/exec/wait system calls. Here’s the program shell.c.

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main() {

printf("Welcome to my shell\n");

char line[1024];

while (1) {

printf("> ");

fgets(line, sizeof(line), stdin);

line[strlen(line)-1] = '\0'; // strip \n

if (strcmp(line, "exit") == 0) // shell built-in

break;

int pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

printf("Executing: %s\n", line);

if (execlp(line, "", NULL) == -1) {

printf("ERROR!\n");

exit(1);

}

} else if (pid > 0) {

int status;

waitpid(pid, &status, 0);

printf("Child exited with %d\n", WEXITSTATUS(status));

} else {

printf("ERROR!\n");

break;

}

}

return 0;

}Compile the program.

gcc shell.c -o shell

And run it.

$ ./shell

Welcome to my shell

> date

Executing: date

Thu Dec 1 14:10:59 UTC 2016

Child exited with 0

> true

Executing: true

Child exited with 0

> false

Executing: false

Child exited with 1

> exit

Have you ever wondered that when you launch a process in the background you only see that it has exited only after a while when you hit Enter?

$ sleep 1 &

[1] 11686

$ # press Enter

[1]+ Done sleep 1

That’s because the shell is waiting for your input. Only when you enter a command does it check for the status of the background processes and show if they’ve been terminated.

TODO

Here is what I’d like to find out more about.

- process state substatuses (

Ss,Ss+,R+, etc.) - kernel threads

/dev/pts- more about memory (

CODE,DATA,SWAP) - figure out time slices length

- Linux scheduler algorithm

- pinning proceses to cores

- write about manual pages

- cpu/memory colors in bars

- process ID limit & fork bomb

lsof,ionice,schedtool

Updates

Here is a list of non-minor corrections and updates since the post was published.

- Idle time in

/proc/uptimeis the sum of all cores (Dec 2, 2016) - My parent/child

printfinzombie.cwas reversed (Dec 2, 2016) apt remove croninstallspostfixbecause of a dependency to an MTA (Dec 3, 2016)idcan load information from other sources (via/etc/nsswitch.conf), not just/etc/passwd(Dec 3, 2016)- Describe

/etc/shadowpassword hash format (Dec 3, 2016) - Use

visudoto edit the/etc/sudoersfile to be safe (Dec 3, 2016) - Explain

MEM%(Dec 3, 2016) - Rewrite the section about load averages (Dec 4, 2016)

- Fix:

kill 1234by default sendsTERMnotINT(Dec 7, 2016) - Explain CPU and memory color bars (Dec 7, 2016)

Final remarks

Please let me know if there is something wrong in this post! I will gladly correct it.

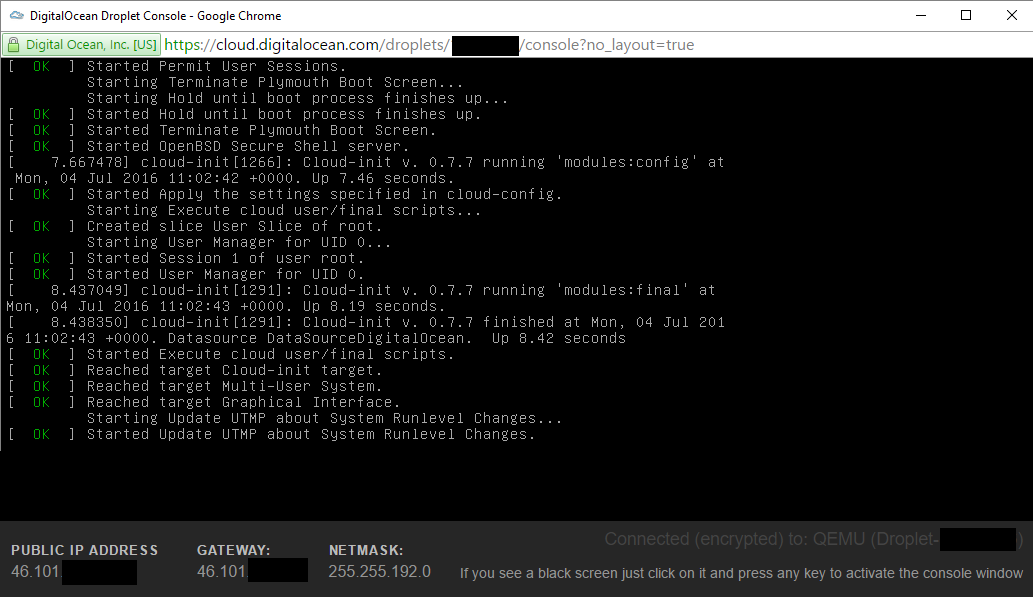

T-shirt

Congratulations on making to the end.

Here’s another screenshot of htop.

This time it’s of a human. It displays your inner processes and the load of your kernel.

Get this t-shirt for yourself or as a gift.

It’s been bought 44 times already (including hoodies, etc.)