communicate effectively by eliminating 5 cognitive distortions

Abstract

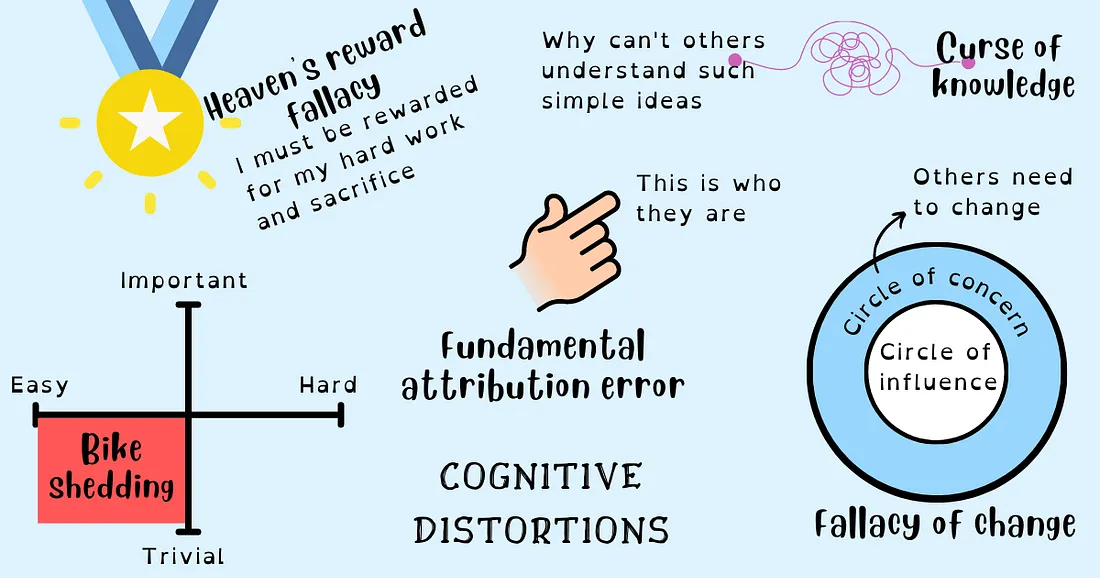

- Cognitive distortions limit your ability to communicate effectively.

- Under the effect of Heaven’s reward fallacy, you expect to be rewarded for all your hard work, effort, and sacrifice. You may show disappointment, frustration, resentment, and dissatisfaction when those rewards do not come.

- The curse of knowledge makes it harder to realize that others don’t share your level of knowledge and expertise. You communicate in a manner that others find very difficult to understand.

- Fundamental attribution error makes you tie other people’s behavior and actions to their character without taking situational and other factors into account.

- The fallacy of change keeps you focused on improving others instead of looking internally at your own behaviors and actions.

- Bikeshedding makes you spend more time attending to trivial matters than prioritizing complex problems.

In part 1 on cognitive distortions, I wrote about the five cognitive distortions that impact your decision-making by impairing your ability to think clearly.

In this article, I will cover five cognitive distortions that impact communication:

- Heaven’s reward fallacy

- Curse of knowledge

- Fundamental attribution error

- Fallacy of change

- Bikeshedding

Let’s get started.

Heaven’s Reward Fallacy

We all expect to be praised for our hard work and effort. We all want to be appreciated, noticed, and rewarded. But a large part of the work we do often goes unnoticed. Always doing good to others does not always come around. Working hard, sacrificing, and exhausting ourselves with endless work does not make success more likely.

Seeking external rewards and external approval only leads to disappointment with feelings of anger, frustration, and resentment because reality often does not align with our expectations.

Those under the influence of heaven’s reward fallacy have a hard time saying no. They think that if they keep doing good to others, others will do good to them, or if they are always helpful, others will also help them out when they need it.

But the world isn’t fair. Constantly giving to others does not guarantee a return.

Example of Heaven’s reward fallacy cognitive distortion

Let’s say you’re leading a big project. You consider this project as your chance to show your skills, prove your worth and get to the next step on the career ladder. So, you work extra hard, compromising on your family time, working even weekends and late nights to ensure nothing gets in the way of its success. But just a few weeks before the final delivery, the company decides to pull the plug on this project.

Restructuring within the organization led to a change in the company strategy — your project, which was once considered highly valuable, is no longer useful.

The thinking mistake — I did what I was asked to do, it’s not my fault that the company changed its strategy — that you must be rewarded for all the hard work and sacrifice you’ve made thus far will only lead to feelings of anger, disappointment, and bitterness when the rewards don’t come.

How to tackle it

To avoid the effect of this cognitive distortion, don’t think of your effort in terms of the specific outcomes you want to achieve. Rather, frame it in terms of your progress, what you’re learning, and how you’re improving.

By seeking internal validation as opposed to the external measure of your worth and redefining your rewards from performance to learning, you can align your actions with your principles and values and direct your energy towards getting better as opposed to seeking a specific job title, reward, or recognition.

In short, detach inputs from outputs.

Curse of knowledge

The curse of knowledge is a cognitive bias in which people who are experts in their specific fields or those knowledgeable in certain areas make the flawed assumption that others have the same background and knowledge on topics as they do.

Being cursed with the knowledge makes sharing it with others ineffective — most people either don’t get it, or the information does not stick. This happens because knowing something makes it harder to imagine that others are not at their level and they still have a lot of catching up to do. Not knowing others’ state of mind creates a disconnect between what they convey and what others understand.

Those under the influence of the curse of knowledge use abstract language, switch between topics without establishing a clear connection, or use phrases and jargon that only people with deep knowledge of the topic understand.

“Lots of us have expertise in particular areas. Becoming an expert in something means that we become more and more fascinated by nuance and complexity. That’s when the curse of knowledge kicks in, and we start to forget what it’s like not to know what we know .” — Chip and Dan Heath, “Made to Stick”

Example of the curse of knowledge cognitive distortion

Let’s say you are a senior engineer tasked with the responsibility to mentor a junior engineer who just joined your team. Under the curse of knowledge, you may skip giving the context, explaining the terminology, or how certain things are done in the team.

Being an expert at your thing and having spent so much time doing it well makes you forget that you were not an expert when you first started. As the junior engineer acts clueless about what you just said or how to do a certain thing, their inability to keep up with your plan adds to your frustration.

How to tackle it

To avoid the effect of this cognitive distortion, use the Feynman technique — communicate as if you’re speaking to a five year old. Focus on the basic concepts and their relationships, stay away from complicated vocabulary and jargon, and use easily accessible words and phrases.

In short, if you’re an expert in a particular area or a leader who wishes to communicate effectively, remember the gap between what you now know and what you knew before and use simple language to communicate your ideas and strategies.

Fundamental attribution error

The fundamental attribution error or attribution bias is a cognitive distortion in which we pass judgment or stamp people as “this is who they are” without analyzing the situational factors contributing to their behavior.

The less we know about someone, the easier it’s for us to label them, attribute their behavior to their character and then stick with those assumptions without considering the limitations and constraints within which they might be operating.

When a coworker declines your meeting invite, do you think they’re rude?

When a colleague refuses to help out, do you call them arrogant?

Judging character this way is a flawed line of thinking. Using limited or incomplete information without considering alternative perspectives or other factors that might have contributed to their behavior can break down communication, impact collaboration, and even cost someone their job.

“The mistake we make in thinking of character as something unified and all-encompassing is very similar to a kind of blind spot in the way we process information.

Psychologists call this tendency the Fundamental Attribution Error (FAE), which is a fancy way of saying that when it comes to interpreting other people’s behavior, human beings invariably make the mistake of overestimating the importance of fundamental character traits and underestimating the importance of situation and context .” — Malcolm Gladwell, “The Tipping Point”

Fundamental attribution error occurs because our brain runs on autopilot, and they choose personal attribution, which is easy and automatic, over situational attribution, which is complex and deliberate. Without engaging in deliberate thinking, we fall for shortcuts.

When we tag people as difficult, incompetent, lazy, careless, or stupid, we don’t see anything wrong with our judgment because we believe in our version of reality.

Example of fundamental attribution error cognitive distortion

Let’s say you’re an executive for an online education company. You have a new team member, Rhea, joining today to head your new business initiatives.

In an early morning meeting with Rhea and other executives, you notice Rhea constantly distracted. She appears lost and keeps checking her phone instead of trying to engage with others. Rhea’s mom is hospitalized. She came to the office since it was her first day at the job but is now worried and waiting to hear back from her husband, who’s at the hospital looking after her mom.

Without speaking to Rhea and understanding why she’s distracted, you may declare her as unreliable, arrogant, or someone who’s just not suited for the role.

How to tackle it

You can’t completely eliminate the fundamental attribution error because it originates out of your brain’s necessity to apply shortcuts which are often necessary and helpful — deliberate thinking in all your interactions is simply not possible because it’s too slow.

But, you can learn to avoid fundamental attribution error when the stakes are high by asking these questions:

- Why does this person behave this way?

- Under what circumstances can I see myself or others behave in a similar manner?

- What situational factors could have contributed to it?

Slow down and pause to find evidence that can point you in a different direction than your default setting.

In short, the map is not the territory. There’s always more to the story than you think.

Fallacy of change

This cognitive distortion is accompanied by the belief that our success and happiness depend on those around us and that changing them is the only way to get what we want.

I can be happy in my job only if my boss stops micromanaging me.

My work can be so much more meaningful only if my teammates stop disagreeing with me and start listening to what I have to say.

Expecting others to change is a fallacy — pressuring others, manipulating them, or encouraging them to change does not guarantee happiness because true happiness is not external. It comes from within.

Thinking others are the source of your problems and expecting everyone else around you to change except you makes you focus on other people’s behaviors and actions — things you can’t control — as opposed to your own behaviors and actions — things within your control.

This is different from showing disappointment in someone’s behavior or pointing out their mistakes — you’re not interested in their improvement for their own sake but out of the desire to get them to do what you want. Trying to control others creates conflict — they may feel attacked or pushed around, further increasing the conflict and making them more resistant to change.

Example of fallacy of change cognitive distortion

You may believe that your team does not appreciate your ideas and reject them without hearing them fully. This makes you resent them. You start withholding and stop sharing your ideas, believing there’s no point in sharing unless your team changes their attitude and starts listening to what you have to say.

Resenting them or expecting them to agree with you will not happen. Instead, shift your focus from “how can I make myself heard?” to “how can I contribute value?”

- Identify what must change about how you convey ideas.

- Is there a gap in your understanding of what the team needs?

- Speak to them about what they dislike about your ideas and how you can improve.

How to tackle it

Instead of demanding others change by assuming that your misery is their fault or your needs can’t be met unless others behave the way you expect them to be, take responsibility for your own actions and decisions — things you did or did not do. Expecting others to change is futile. The only person you can change is YOU.

“There’s nothing wrong with a person’s temperament. But there could be a lot wrong with their behaviors, attitudes, and choices. They’ve been making those choices for a long time, so it’s not something we can easily change. We can’t guarantee that they’ll make good choices, but we can choose how we respond to those choices.” — Mike Bechtle

In short, direct your energy towards your own behaviors and actions, and don’t waste it trying to change others.

Bikeshedding

Bikeshedding cognitive distortion, also known as Parkinson’s law of triviality shows up when we devote a disproportionate amount of our time to menial and trivial matters while leaving important matters unattended.

We have all been part of meetings where minor or unimportant issues take up the majority of time, leaving less time for more complex issues, or where the discussion gets sidetracked to trivial matters leaving complicated problems to receive little attention.

This happens because discussing a simple issue feels comfortable — it’s easier to understand, within our circle of competence, requires less cognitive resources, and allows us to share our opinion with others. Complex issues, on the other hand, need more work — unknowns, uncertainty, and the nature of the problem demand careful analysis. You may not fully understand the complexity or find it risky to voice your opinion.

Bikeshedding also affects you personally when you keep putting off complex tasks while ticking off easier ones on your to-do list. Prioritizing trivial work over more important ones only gives you an illusion of productivity. Tasks that seem easier take less time to complete making you believe that you are being productive, but putting off work that’s more valuable in the long run while allocating more time to menial tasks is a waste of your time.

Example of bikeshedding cognitive distortion

Let’s say you’re a senior engineer in a software company tasked with the design of a new product. The task is complex and involves many unknowns.

Instead of spending the majority of your time with those complex elements (what are the failure points, what’s acceptable fault tolerance, tech stack to use), you spend more time thinking about the name of the database tables, deciding API endpoints, refactoring existing code, or taking on other easy tasks.

Bikeshedding is in effect if you keep doing easy work at the cost of putting off important and complex tasks which are difficult to deal with but add more value to the project.

How to tackle it

To avoid bikeshedding in a group setting, set a clear purpose for all meetings with a single agenda item and ask the group to point out when the discussion goes off track.

In “The Art of Gathering,” Priya Parker says that “specificity” is a crucial ingredient for a successful discussion. In other words, every meeting needs to have a focused and clear purpose. Thinking about the purpose of the meeting also helps you decide who to invite — better keep those without relevant knowledge and experience off the list.

Personally, for your own work, being aware of bikeshedding is a starting point to counter its effect — stop prioritizing trivial matters over important work.

In short, difficult problems may take longer to solve but are also more effective. They are the ones that move you forward by helping you get over your fears, embrace challenges, and master new skills.

Summary

- Cognitive distortions limit your ability to communicate effectively.

- Under the effect of Heaven’s reward fallacy, you expect to be rewarded for all your hard work, effort, and sacrifice. You may show disappointment, frustration, resentment, and dissatisfaction when those rewards do not come.

- The curse of knowledge makes it harder to realize that others don’t share your level of knowledge and expertise. You communicate in a manner that others find very difficult to understand.

- Fundamental attribution error makes you tie other people’s behavior and actions to their character without taking situational and other factors into account.

- The fallacy of change keeps you focused on improving others instead of looking internally at your own behaviors and actions.

- Bikeshedding makes you spend more time attending to trivial matters than prioritizing complex problems.