Load balancing

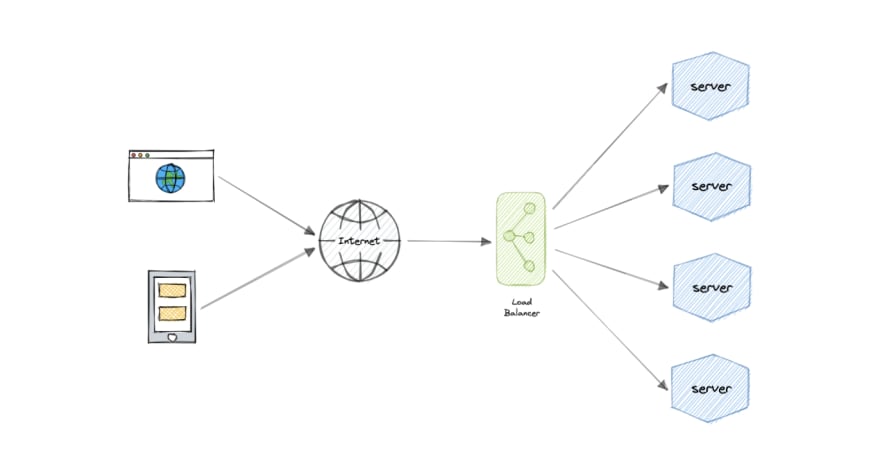

Load balancing lets us distribute incoming network traffic across multiple resources ensuring high availability and reliability by sending requests only to resources that are online. This provides the flexibility to add or subtract resources as demand dictates.

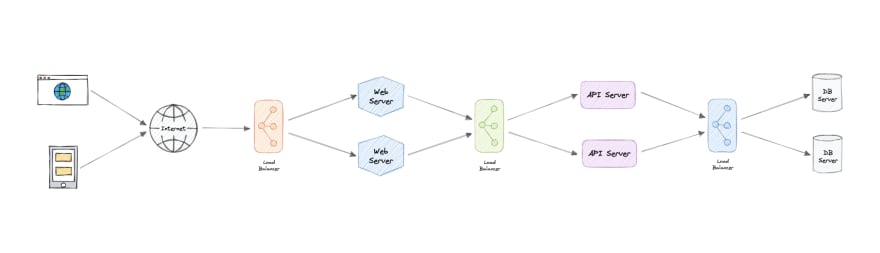

For additional scalability and redundancy, we can try to load balance at each layer of our system:

For additional scalability and redundancy, we can try to load balance at each layer of our system:

But why?

Modern high-traffic websites must serve hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of concurrent requests from users or clients. To cost effectively scale to meet these high volumes, modern computing best practice generally requires adding more servers.

A load balancer can sit in front of the servers and route client requests across all servers capable of fulfilling those requests in a manner that maximizes speed and capacity utilization and ensures that no one server is overworked, which could degrade performance. If a single server goes down, the load balancer redirects traffic to the remaining online servers. When a new server is added to the server group, the load balancer automatically starts to send requests to it.

Workload distribution

This is the core functionality provided by a load balancer and has several common variations:

- Host-based: Distributes requests based on the requested hostname.

- Path-based: Using the entire URL to distribute requests as opposed to just the hostname.

- Content-based: Inspects the message content of a request. This allows distribution based on content such as the value of a parameter.

Layers

Generally speaking, load balancers operate at one of the two levels:

Network layer

This is the load balancer that works at the network’s transport layer, also known as layer 4. This performs routing based on networking information such as IP addresses and is not able to perform content-based routing. These are often dedicated hardware devices that can operate at high speed.

Application layer

This is the load balancer that operates at the application layer, also known as layer 7. Load balancers can read requests in their entirety and perform content-based routing. This allows the management of load based on a full understanding of traffic.

Types

Let’s look at different types of load balancers:

Software

Software load balancers usually are easier to deploy than hardware versions. They also tend to be more cost-effective and flexible, and they are used in conjunction with software development environments. The software approach gives us the flexibility of configuring the load balancer to our environment’s specific needs. The boost in flexibility may come at the cost of having to do more work to set up the load balancer. Compared to hardware versions, which offer more of a closed-box approach, software balancers give us more freedom to make changes and upgrades.

Software load balancers are widely used and are available either as installable solutions that require configuration and management or as a managed cloud service.

Hardware

As the name implies, a hardware load balancer relies on physical, on-premises hardware to distribute application and network traffic. These devices can handle a large volume of traffic but often carry a hefty price tag and are fairly limited in terms of flexibility.

Hardware load balancers include proprietary firmware that requires maintenance and updates as new versions and security patches are released.

DNS

DNS load balancing is the practice of configuring a domain in the Domain Name System (DNS) such that client requests to the domain are distributed across a group of server machines.

Unfortunately, DNS load balancing has inherent problems limiting its reliability and efficiency. Most significantly, DNS does not check for server, network outages, or errors, and so always returns the same set of IP addresses for a domain even if servers are down or inaccessible

Routing Algorithms

Now, let’s discuss commonly used routing algorithms:

- Round-robin: Requests are distributed to application servers in rotation.

- Weighted Round-robin: Builds on the simple Round-robin technique to account for differing server characteristics such as compute and traffic handling capacity using weights that can be assigned via DNS records by the administrator.

- Least Connections: A new request is sent to the server with the fewest current connections to clients. The relative computing capacity of each server is factored into determining which one has the least connections.

- Least Response Time: Sends requests to the server selected by a formula that combines the fastest response time and fewest active connections.

- Least Bandwidth: This method measures traffic in megabits per second (Mbps), sending client requests to the server with the least Mbps of traffic.

- Hashing: Distributes requests based on a key we define, such as the client IP address or the request URL.

Advantages

Load balancing also plays a key role in preventing downtime, other advantages of load balancing include the following:

- Scalability

- Redundancy

- Flexibility

- Efficiency

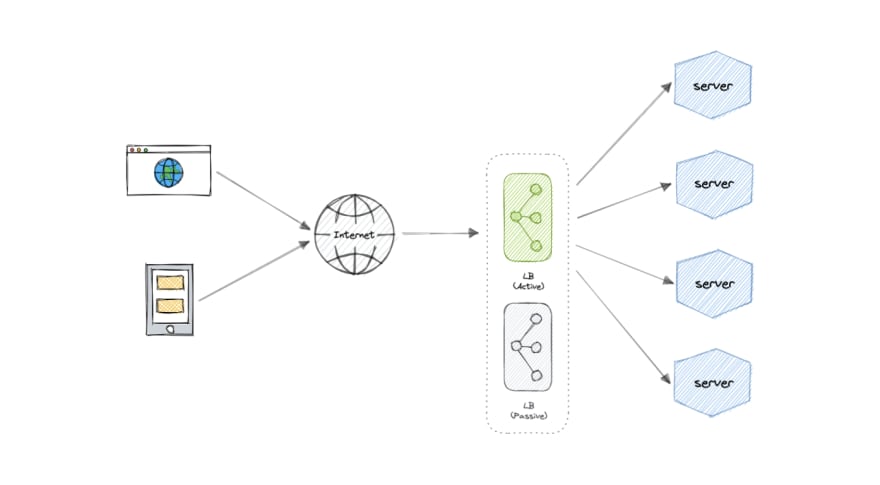

Redundant load balancers

As you must’ve already guessed, the load balancer itself can be a single point of failure. To overcome this, a second or N number of load balancers can be used in a cluster mode.

And, if there’s a failure detection and the active load balancer fails, another passive load balancer can take over which will make our system more fault-tolerant.

Features

Here are some commonly desired features of load balancers:

- Autoscaling: Starting up and shutting down resources in response to demand conditions.

- Sticky sessions: The ability to assign the same user or device to the same resource in order to maintain the session state on the resource.

- Healthchecks: The ability to determine if a resource is down or performing poorly in order to remove the resource from the load balancing pool.

- Persistence connections: Allowing a server to open a persistent connection with a client such as a WebSocket.

- Encryption: Handling encrypted connections such as TLS and SSL.

- Certificates: Presenting certificates to a client and authentication of client certificates.

- Compression: Compression of responses.

- Caching: An application-layer load balancer may offer the ability to cache responses.

- Logging: Logging of request and response metadata can serve as an important audit trail or source for analytics data.

- Request tracing: Assigning each request a unique id for the purposes of logging, monitoring, and troubleshooting.

- Redirects: The ability to redirect an incoming request based on factors such as the requested path.

- Fixed response: Returning a static response for a request such as an error message.

Examples

Following are some of the load balancing solutions commonly used in the industry: