circuit breaker

The basic idea behind the circuit breaker is very simple. We wrap a protected function call in a circuit breaker object, which monitors for failures. Once the failures reach a certain threshold, the circuit breaker trips, and all further calls to the circuit breaker return with an error, without the protected call being made at all. Usually, we’ll also want some kind of monitor alert if the circuit breaker trips.

Why do we need circuit breaking?

It’s common for software systems to make remote calls to software running in different processes, probably on different machines across a network. One of the big differences between in-memory calls and remote calls is that remote calls can fail, or hang without a response until some timeout limit is reached. What’s worse if we have many callers on an unresponsive supplier, then we can run out of critical resources leading to cascading failures across multiple systems.

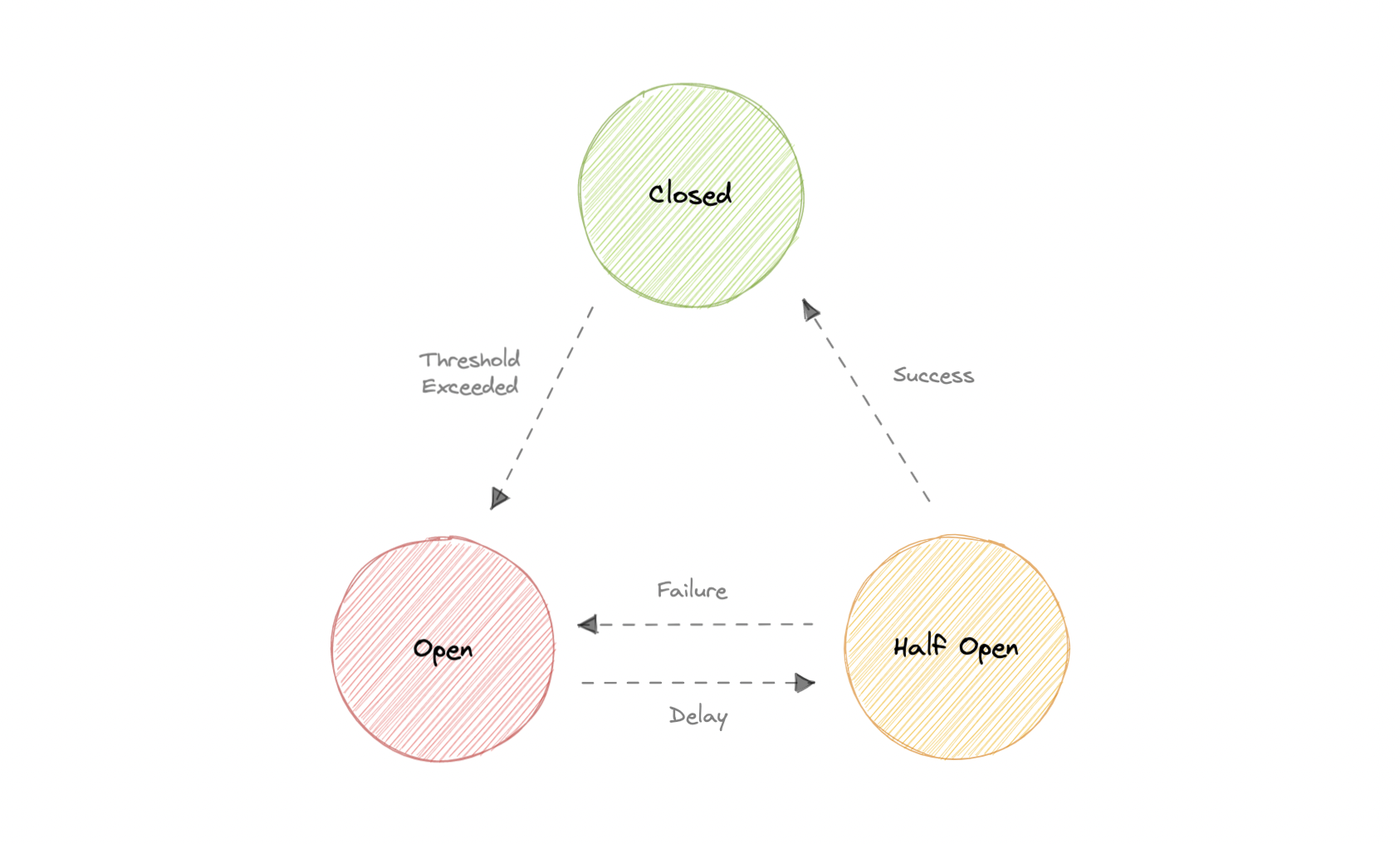

States

Let’s discuss circuit breaker states:

Closed

When everything is normal, the circuit breakers remain closed, and all the request passes through to the services as normal. If the number of failures increases beyond the threshold, the circuit breaker trips and goes into an open state.

Open

In this state circuit breaker returns an error immediately without even invoking the services. The Circuit breakers move into the half-open state after a certain timeout period elapses. Usually, it will have a monitoring system where the timeout will be specified.

Half-open

In this state, the circuit breaker allows a limited number of requests from the service to pass through and invoke the operation. If the requests are successful, then the circuit breaker will go to the closed state. However, if the requests continue to fail, then it goes back to the open state.