learn RESTful API design ideals

src: RESTful API Design Tips from Experience - 2022-03-12

Abstract

- versioning in path, e.g.

GET api.myservice.com/v1/posts- HTTP methods

GETfor fetching data.POSTfor adding data.PUTfor updating data (as a whole object).PATCHfor updating data (with partial information for the object).DELETEfor deleting data.- use plural, e.g.

GET /v1/posts/:id/attachments/:id/comments- use nesting relationship filtering

/posts/x/attachmentsis better than/attachments?postId=x/posts/x/attachments/y/commentsis so much better than/comments?postId=x&attachmentId=y- keep your API as flat as possible

- allow

/posts/:id/commentsto fetch the comments for a post based on relationship- also offer

/comments/:idto allow editing of comments without needing a handle for the post for every single route- use authorization context to filter

- Nest a

/postsrelationship under/mewithGET /me/posts, or- Use the existing

/postsendpoint but filter with query string,GET /posts?user=<id of self>, or- Reuse

/poststo show only your own posts, and expose public posts withGET /feed/posts.- use a

meendpoint

- updating user preferences allow

PATCH /meto change those intrinsic values- provide pagination

- from parameter

- next page token

- envelop your data responses

- be consistent in the request and response format (e.g. JSON in request AND response)

- return the updated object

- use 204 for deletion

- use HTTP status code and error responses

- for data errors

400for when the requested information is incomplete or malformed, e.g. if the422for when the requested information is okay, but invalid, e.g. if thepasswordfield is too short, or if the404for when everything is okay, but the resource doesn’t exist.409for when a conflict of data exists, even with valid information, if the- for auth errors

401for when an access token isn’t provided, or is invalid.403for when an access token is valid, but requires more privileges.- for standard statuses

200for when everything is okay.204for when everything is okay, but there’s no content to return.500for when the server throws an error, completely unexpected.- authentication

- use self-extending session tokens

- simply use a

/sessionsresource endpoint to exchange login credentials for a single unique session token (usinguuid4) which is hashed and stored as a database row- jwt, refresh tokens, … too much hassle to invalidate them

- avoid password composition rules

- use a healthcheck endpoint

We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master.

As I write this, I chuckle to myself in seeing a great parallel behind myself referencing Hemingway’s quote from someone else; the sheer notion that I need not labour away at creating a different implementation of the passage with similar functionality for the result value (or in this case, meaning) is a literary testament to code reuse!

But I’m not here to write about the benefits of code packages, but more to mention some of the traits I’ve come to appreciate, and actively implement in present and future projects. And of these features and implementation details, I grow my own package of API rules and primitives.

From publishing this article, many threads of discussion in channels such as Reddit have helped me adjust and tweak some of my explanations and stances on API design. I would like to thank all who have contributed to the discussion, and I hope this helps build this article into a more valuable resource for others! (Edit: 9/June/2019) And now it’s been two years since I first published this article and it’s been incredible to see that it’s been viewed 150,000+ times and received thousands of likes and shares, and once again I want express my gratitude to all my readers and followers!

Versioning

If you’re going to develop an API for any client service, you’re going to want to prepare yourself for eventual change. This is best realized by providing a “version-namespace” for your RESTful API.

We do this with simply adding the version as a prefix to all URLs.

GET www.myservice.com/api/v1/posts

However, through studying other API implementations, I’ve grown to like a shorter URL style offered by accessing the API as part of a subdomain, and then dropping the /api from the route; shorter and more concise is better.

GET api.myservice.com/v1/posts

Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS)

It is important to consider that when placing your API into a different subdomain such as api.myservice.com it will require implementing CORS for your backend if you plan to host your frontend site at www.myservice.com and expect to use fetch requests without throwing No Access-Control-Allow-Origin header is present errors.

Routes

When building your routes you need to think of your endpoints as groups of resources from which you may read, add, edit and delete from and these actions are encapsulated as HTTP methods.

Use HTTP Methods

Use methods such as:

GETfor fetching data.POSTfor adding data.PUTfor updating data (as a whole object).PATCHfor updating data (with partial information for the object).DELETEfor deleting data.

I would like to add that I think PATCH is great way to cut down the size of requests to change parts of bigger objects, but also that it fits well with commonly implemented auto-submit/auto-save fields.

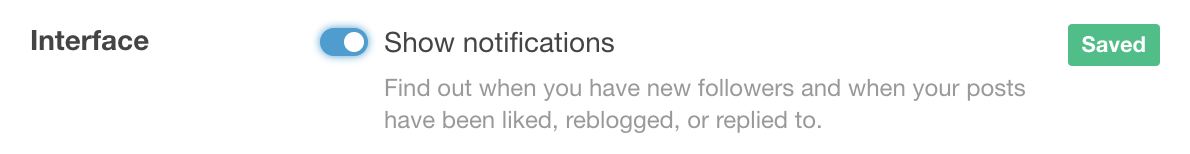

A nice example of this is with Tumblr’s “Dashboard Settings” screen, where non-critical options about the user experience of the service can be edited and saved, per item, without the need of a final form submission button. It is simply a much more organic way to interact with the user’s preference data.

The “Saved” tag appears and then disappears shortly after modifying the option.

Use Plurals

It makes semantic sense when you request many posts from /posts.

And for goodness sake don’t consider /post/all with /post/:id!

// DO: plurals are consistent and make sense

GET /v1/posts/:id/attachments/:id/comments

// DON’T: is it just one comment? is it a form? etc.

GET /v1/post/:id/attachment/:id/comment

In cases like these you should simply try to get as close to plural as you can!

“I like the idea of using plurals for resource names, but sometimes you get names that can’t be pluralised.” (source)

Use Nesting for Relationship Filtering

Query strings should be used for further filtering results beyond the initial grouping of a logical set offered by a relationship.

Aim to design endpoint paths that avoid unnecessary query string parameters as they are generally harder to read and to work with when compared to paths whose structure promotes an initial relationship-based filtering and grouping of such items the deeper it goes.

This

/posts/x/attachmentsis better than/attachments?postId=x. And this/posts/x/attachments/y/commentsis so much better than/comments?postId=x&attachmentId=y.

Use More of your “Route-Space”

You should aim to keep your API as flat as possible and not crowd your resource paths. Allow yourself to provide flat routes to all update/delete your resources such as in the case of posts having comments, allow /posts/:id/comments to fetch the comments for a post based on relationship, but also offer /comments/:id to allow editing of comments without needing a handle for the post for every single route.

- Longer paths for creating/fetching nested resources by relationship

- Shorter paths for updating/deleting resources based on their

id.

Use the Authorization Context to Filter

When it comes to providing an endpoint to access all of a user’s own resources (e.g. all my own posts) you might end up with many ways to provide that information, it’s up to you what best suits your application.

- Nest a

/postsrelationship under/mewithGET /me/posts, or - Use the existing

/postsendpoint but filter with query string,GET /posts?user=<id of self>, or - Reuse

/poststo show only your own posts, and expose public posts withGET /feed/posts.

Use a “Me” Endpoint

Have an endpoint like GET /me to deliver basic data about the user as distinguished through the Authorisation header. This can include info about the user’s permissions/scopes/groups/posts/sessions etc. that allow the client to show/hide elements and routes based on your permissions.

When it comes to providing endpoints for updating user preferences allow PATCH /me to change those intrinsic values.

Provide Pagination

Pagination is really important because you don’t want a simple request to be incredibly expensive if there are thousands of rows of results. It seems obvious, but many neglect this functionality.

There are multiple ways to do this:

“From” Parameter

Arguably the easiest to implement, where the API accepts a from query string parameter and then returns a limited number of results from that offset (commonly 20 results).

Also best to provide a limit parameter which has a hard-maximum, such as the case of Twitter, with a maximum of1000 and default limit of 200.

Next Page Token

Google’s Places API returns a next_page_token in its responses if there is more information available beyond the limited 20 results per page. It then accepts pagetoken as a parameter for a new request which continues returning more results with a new next_page_token until it is exhausted. Twitter does a similar thing instead using a param called next_cursor.

Responses

Use Envelopes

“I do not like enveloping data. It just introduces another key to navigate a potentially dense tree of data. Meta information should go in headers.”

“One argument for nesting data is to provide two distinct root keys to indicate the success of the response,

_*data*_and_*error*_. However, I delegate this distinction to the HTTP status codes in cases of errors.”

Originally, I held the stance that enveloping data is not necessary, and that HTTP provided an adequate “envelope” in itself for delivering a response. However, after reading through responses on Reddit, various vulnerabilities and potential hacks can occur if you do not envelope JSON arrays.

You should envelope your data responses!

// DO: enveloped

{

data: [

{ … },

{ … },

// …

]

}

// DON’T non-enveloped

[

{ … },

{ … },

// …

]

“Additionally, if you like to use a tool like normalizr for parsing data from responses client-side, removing an envelope removes the need for constantly extracting the data from the response payload to pass it to be normalised.”

On the contrary, providing an extra key for accessing your data allows for reliably checking if anything was actually returned, and if not, may refer to a non-colliding error key separate from the body of a response.

It is also important to consider that unlike some, languages such as JavaScript will evaluate empty objects as true! Hence it is important to not return an empty object for error as part of a response in the case of:

// enveloped, error extraction from payload

const { data, error } = payload

// processing errors if they exist

if (error) { throw … }

// otherwise

const normalizedData = normalize(data, schema)

JSON Responses and Requests

“Everything should be serialized into JSON. If you’re expecting JSON from the server, be polite, and provide the server with JSON. Consistency!”

Obviously “everything” is an overstatement as some comments point out, but was intended to refer to any simple, plain object that should be serialized for the process of consuming and/or returning from the API.

It is essential to define your media types through headers on both responses and requests for a RESTful API. When dealing with JSON ensure that you include a Content-Type: application/json header, and respectively for other response types, be it CSVs or binaries.

Return the Updated Object

When updating any resource through a PUT or PATCH it’s good practice to return the updated resource in response to a successful POST , PUT , or PATCH request!

Use 204 for Deletions

There have been cases where I’ve had nothing to return from the success of an action (i.e. DELETE), however I feel that returning an empty object can in some languages (such as Python) be evaluated as false and may not be as obvious to a human debugging their application.

Support the 204 — No Content response status code in cases where the request was successful but has no content to return. The envelope of the response, coupled with a 2XX HTTP success code is enough to indicate a successful response without arbitrary “information”.

DELETE /v1/posts/:id

// response - 204

{

“data”: null

}

Use HTTP Status Codes and Error Responses

Because we are using HTTP methods, we should use HTTP status codes. Although a challenge here is to select a distinct slice of these codes, and then depend on response data to detail any response errors. Keeping a small set of codes helps you consume and handle errors consistently.

I like to use:

for Data Errors

400for when the requested information is incomplete or malformed.422for when the requested information is okay, but invalid.404for when everything is okay, but the resource doesn’t exist.409for when a conflict of data exists, even with valid information.

for Auth Errors

401for when an access token isn’t provided, or is invalid.403for when an access token is valid, but requires more privileges.

for Standard Statuses

200for when everything is okay.204for when everything is okay, but there’s no content to return.500for when the server throws an error, completely unexpected.

Furthermore, returning responses after these errors is also very important. I want to consider not only the presentation of the status itself, but also a reason behind it.

In the case of trying to create a new account, imagine we provide an email and password. Of course we would like to have our client app prevent any requests with an invalid email, or password that is too short, but outsiders have as much access to the API as we do from our client app when it’s live.

- If the

emailfield is missing, return a400. - If the

passwordfield is too short, return a422. - If the

emailfield isn’t a valid email, return a422. - If the

emailis already taken, return a409.

“It’s much better to specify a more specific 4xx series code than just plain 400. I understand that you can put whatever you want in the response body to break down the error but codes are much easier to read at a glance.” (source)

Now from these cases, two errors returned 422s regardless of their reasons being different. This is why we need an error code, and maybe even an error description. It’s important to make a distinction between code and description as I intend to have code as a machine consumable constant, and message as a human consumable string that may change.

In the case of per-field errors, the presence of the field as a key in the error is enough of a “code” to indicate that it is a target of a validation error.

Field Validation Errors

For returning those per field errors, it may be returned as:

POST /v1/register

// request

{

“email”: “end@@user.comx"

"password”: “abc”

}

// response - 422

{

“error”: {

“code”: “FIELDS_VALIDATION_ERROR”,

“message”: “One or more fields raised validation errors."

"fields”: {

“email”: “Invalid email address.”,

“password”: “Password too short.“

}

}

}

Operational Validation Errors

And for returning operational validation errors:

POST /v1/register

// request

{

“email”: “end@user.com”,

“password”: “password”

}

// response - 409

{

“error”: {

“code”: “EMAIL_ALREADY_EXISTS”,

“message”: “An account already exists with this email.“

}

}

The message can act as a fallback human-readable error message to help understand the request when developing, and also in the case an appropriate localisation string implementation cannot be used.

This way, your fetch logic watches out for non-200 errors, and can then straight-up check the error key from the response and then compare it to any further logic in the client app.

Authentication

Modern stateless, RESTful APIs implement authentication with tokens most commonly provided through the Authorization header (or even an access_token query param).

Use Self-extending Session Tokens

Originally I thought that issuing JWTs for regular API requests was a great way to handle authentication — until I wanted to invalidate those tokens.

In my last revision of this post (and detailed in a separate post) I offered a way for JWTs to be reissued through an additionally stored client secret “Refresh Token” (RT) which was to be exchanged for new JWTs. However in order to expire these JWTs they each contained a reference to the issuing RT so if the RT was invalided/deleted so would the JWT. However this mechanism defeats the statelessness of the JWT itself…

My solution now is to simply use a /sessions resource endpoint to exchange login credentials for a single unique session token (using uuid4) which is hashed and stored as a database row. Just like many moderns apps, the token doesn’t need to be reissued unless there is a long period of inactivity (similar to session timeout, but to the scale of weeks). After initial authentication, every future request bumps the life of the token in a self-extending manner as long as it hasn’t expired.

Session Creation — Logging In

A normal login process would look like:

- Receive email/password combination with

POST /sessions, treatingsessionsas just another resource. - Check the email/password-hash against the database.

- Create a new

sessiondatabase row that contains a hasheduuid4()as atoken. - Return the non-hashed

tokenstring to the client.

Session Renewal

In this flow tokens don’t need to be explicitly renewed or reissued. That’s because the API extends the life of the token if its still valid every request, saving regular users from ever having a session expire for them.

Whenever a token is received by the API i.e. through an Authorization header:

- Receive the

tokeni.e. from theAuthorizationheader. - Compare against the

token’s hash, if there is no matchingsessionrow, raise an authentication error. - Check the

updated_atproperty of thesession, if now if greater thanupdated_at + session_lifethe session is considered expired, delete thesessionrow, raise an authentication error. - If it exists and is still valid from

updated_attime, set theupdated_attime tonow()to renew the token.

Session Management

Because all sessions are tracked as database rows mapped to a user, a user can see all their active sessions similar to Facebook’s account security sessions view. You can also chose to include any associated metadata you have chosen to collected when initially creating a session such as the browser’s User Agent, IP address etc. And

Fetching all your sessions is as simple as:

GET /sessionsto return all sessions associated with your user via theAuthorizationheader.

Session Termination — Logging Out

And because you have handles to your sessions you can terminate them to invalidate unauthorised or unwanted access to your account. And logging out would simply be terminating the client’s session and purging the session from the client.

- Receive the

tokenas part of aDELETE /sessions/idrequest. - Compare against the

token’s hash, delete the matching session row.

Avoid Password Composition Rules

After doing a lot of research into password rules, I’ve come to agree that password rules are bullshit and are part of NIST’s “don’ts”, especially considering that password composition rules help narrow down valid passwords based on their validity rules.

I’ve collated some of the best points (from the above links) for password handling:

- Only enforce a minimum unicode password length (min 8–10).

- Check against common passwords (“password12345”)

- Check for basic entropy (don’t allow “aaaaaaaaaaaaa”).

- Don’t use password composing rules (at least one “!@#$%&”).

- Don’t use password hints (rhymes with “assword”).

- Don’t use knowledge-based authentication (“security” questions).

- Don’t expire passwords without reason.

- Don’t use SMS for two-factor authentication.

- Use a password salt of 32-bits or more.

These “don’ts” should make password validation much easier!

Meta

Use a “Health-Check” Endpoint

Through developing with AWS, it been necessary to provide a way to output a simple response that can indicate that the API instance is alive and does not need to be restarted. It’s also useful for easily checking what version of the API is on any machine at any time, without authentication.

GET /v1

// response - 200

{

"status": "running",

"version": "fdb1d5e"

}

I provide status and version (which refers to the git commit ref of the API at the time it was built). It’s also worth mentioning that this value is not derived from an active .git repo being bundled with the APIs container for EC2. Instead, it is read (and stored in memory) on initialisation from a version.txt file (which is generated from the build process), and defaults to __UNKNOWN__ in case of a read error, or the file does not exist.

What’s an API?

Before we even get into API technologies, let’s first understand what is an API.

An API is a set of definitions and protocols for building and integrating application software. It’s sometimes referred to as a contract between an information provider and an information user establishing the content required from the producer and the content required by the consumer.

In other words, if you want to interact with a computer or system to retrieve information or perform a function, an API helps you communicate what you want to that system so it can understand and complete the request.

REST

A REST API (also known as RESTful API) is an application programming interface that conforms to the constraints of REST architectural style and allows for interaction with RESTful web services. REST stands for Representational State Transfer and it was first introduced by Roy Fielding in the year 2000.

In REST API, the fundamental unit is a resource.

Concepts

Let’s discuss some concepts of a RESTful API.

Constraints

In order for an API to be considered RESTful, it has to conform to these architectural constraints:

- Uniform Interface: There should be a uniform way of interacting with a given server.

- Client-Server: A client-server architecture managed through HTTP.

- Stateless: No client context shall be stored on the server between requests.

- Cacheable: Every response should include whether the response is cacheable or not and for how much duration responses can be cached at the client-side.

- Layered system: An application architecture needs to be composed of multiple layers.

- Code on demand: Return executable code to support a part of your application. (optional)

HTTP Verbs

HTTP defines a set of request methods to indicate the desired action to be performed for a given resource. Although they can also be nouns, these request methods are sometimes referred to as HTTP verbs. Each of them implements a different semantic, but some common features are shared by a group of them.

Below are some commonly used HTTP verbs:

- GET: Request a representation of the specified resource.

- HEAD: Response is identical to a

GETrequest, but without the response body. - POST: Submits an entity to the specified resource, often causing a change in state or side effects on the server.

- PUT: Replaces all current representations of the target resource with the request payload.

- DELETE: Deletes the specified resource.

- PATCH: Applies partial modifications to a resource.

HTTP response codes

HTTP response status codes indicate whether a specific HTTP request has been successfully completed.

There are five classes defined by the standard:

- 1xx - Informational responses.

- 2xx - Successful responses.

- 3xx - Redirection responses.

- 4xx - Client error responses.

- 5xx - Server error responses.

For example, HTTP 200 means that the request was successful.

Advantages

Let’s discuss some advantages of REST API:

- Simple and easy to understand.

- Flexible and portable.

- Good caching support.

- Client and server are decoupled.

Disadvantages

Let’s discuss some disadvantages of REST API:

- Over-fetching of data.

- Sometimes multiple round trips to the server are required.

Use cases

REST APIs are pretty much used universally and are the default standard for designing APIs. Overall REST APIs are quite flexible and can fit almost all scenarios.

Example

Here’s an example usage of a REST API that operates on a users resource.

| URI | HTTP verb | Description |

|---|---|---|

| /users | GET | Get all users |

| /users/{id} | GET | Get a user by id |

| /users | POST | Add a new user |

| /users/{id} | PATCH | Update a user by id |

| /users/{id} | DELETE | Delete a user by id |

There is so much more to learn when it comes to REST APIs, I will highly recommend looking into Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State (HATEOAS).