database transactions

A transaction is a series of database operations that are considered to be a “single unit of work”. The operations in a transaction either all succeed, or they all fail. In this way, the notion of a transaction supports data integrity when part of a system fails. Not all databases choose to support ACID transactions, usually because they are prioritizing other optimizations that are hard or theoretically impossible to implement together.

Usually, relational databases support ACID transactions, and non-relational databases don’t (there are exceptions).

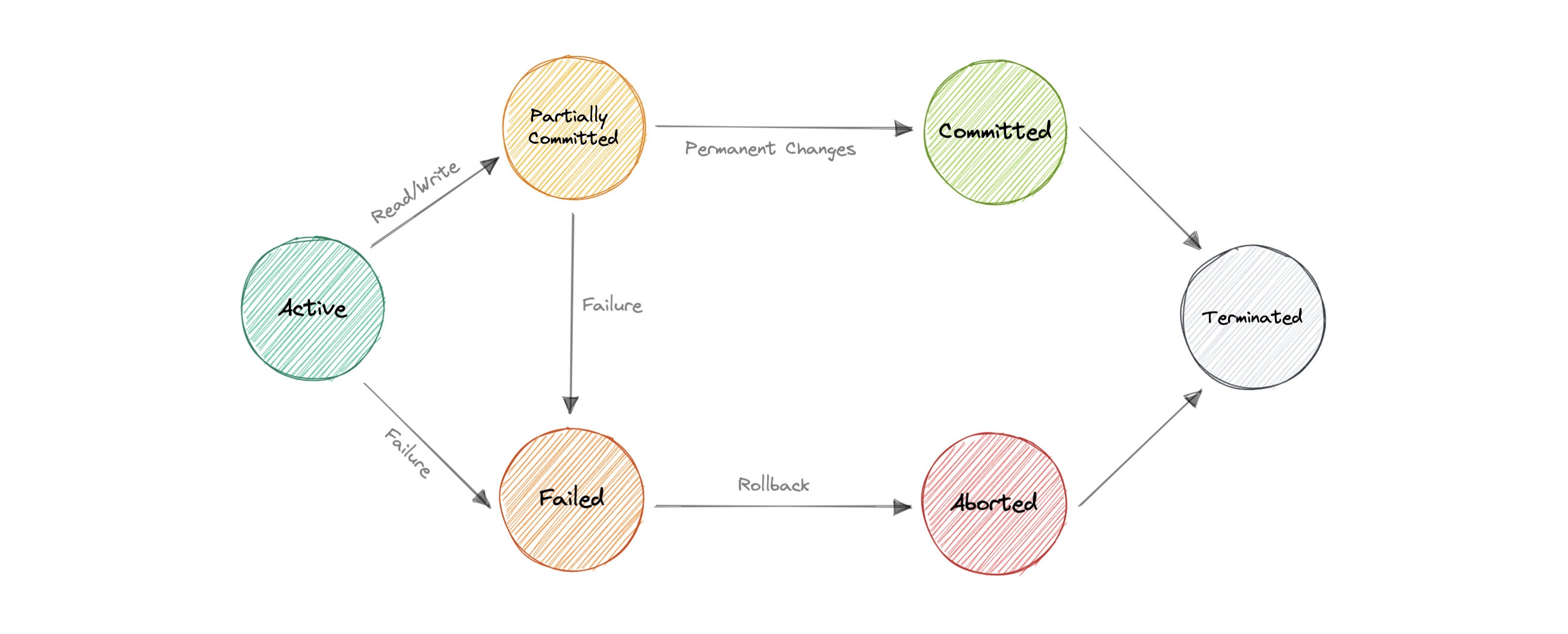

States

A transaction in a database can be in one of the following states:

Active

In this state, the transaction is being executed. This is the initial state of every transaction.

Partially Committed

When a transaction executes its final operation, it is said to be in a partially committed state.

Committed

If a transaction executes all its operations successfully, it is said to be committed. All its effects are now permanently established on the database system.

Failed

The transaction is said to be in a failed state if any of the checks made by the database recovery system fails. A failed transaction can no longer proceed further.

Aborted

If any of the checks fail and the transaction has reached a failed state, then the recovery manager rolls back all its write operations on the database to bring the database back to its original state where it was prior to the execution of the transaction. Transactions in this state are aborted.

The database recovery module can select one of the two operations after a transaction aborts:

- Restart the transaction

- Kill the transaction

Terminated

If there isn’t any roll-back or the transaction comes from the committed state, then the system is consistent and ready for a new transaction and the old transaction is terminated. e

Distributed Transactions

A distributed transaction is a set of operations on data that is performed across two or more databases. It is typically coordinated across separate nodes connected by a network, but may also span multiple databases on a single server.

Why do we need distributed transactions?

Unlike an ACID transaction on a single database, a distributed transaction involves altering data on multiple databases. Consequently, distributed transaction processing is more complicated, because the database must coordinate the committing or rollback of the changes in a transaction as a self-contained unit.

In other words, all the nodes must commit, or all must abort and the entire transaction rolls back. This is why we need distributed transactions.

Now, let’s look at some popular solutions for distributed transactions:

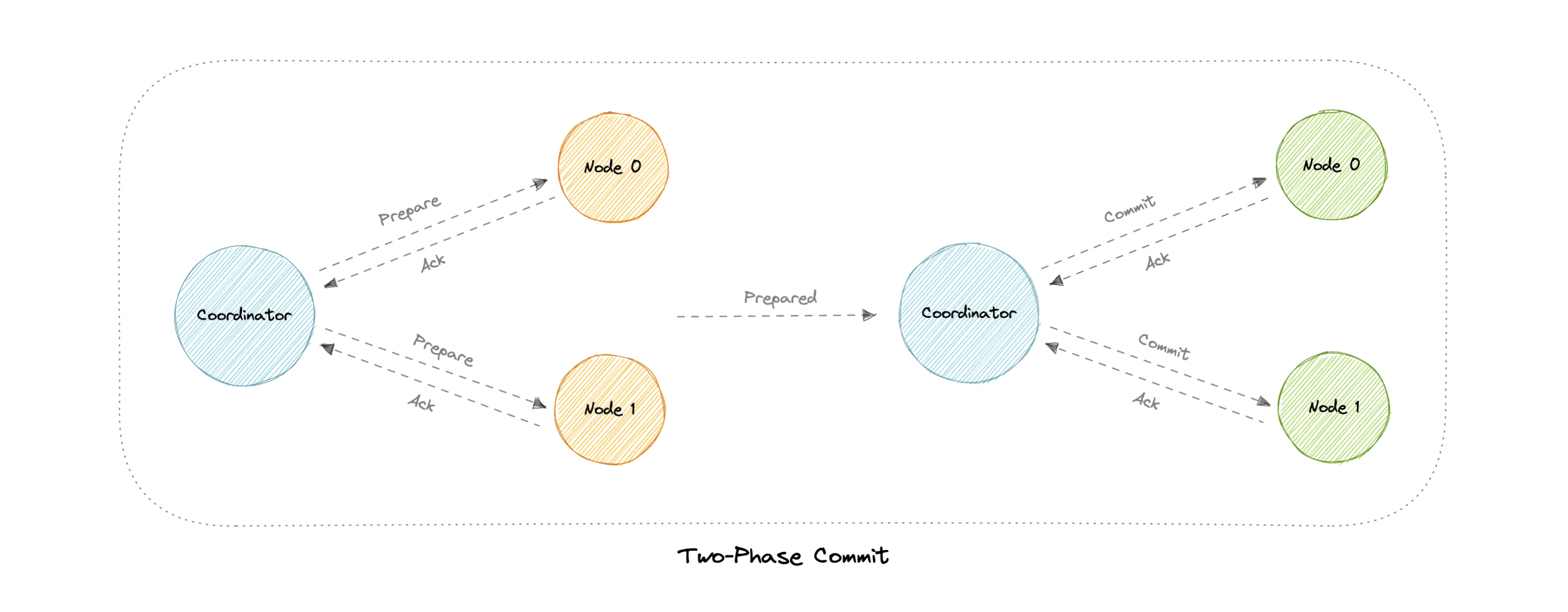

Two-Phase commit

The two-phase commit (2PC) protocol is a distributed algorithm that coordinates all the processes that participate in a distributed transaction on whether to commit or abort (roll back) the transaction.

This protocol achieves its goal even in many cases of temporary system failure and is thus widely used. However, it is not resilient to all possible failure configurations, and in rare cases, manual intervention is needed to remedy an outcome.

This protocol requires a coordinator node, which basically coordinates and oversees the transaction across different nodes. The coordinator tries to establish the consensus among a set of processes in two phases, hence the name.

Phases

Two-phase commit consists of the following phases:

Prepare phase

The prepare phase involves the coordinator node collecting consensus from each of the participant nodes. The transaction will be aborted unless each of the nodes responds that they’re prepared.

Commit phase

If all participants respond to the coordinator that they are prepared, then the coordinator asks all the nodes to commit the transaction. If a failure occurs, the transaction will be rolled back.

Problems

Following problems may arise in the two-phase commit protocol:

- What if one of the nodes crashes?

- What if the coordinator itself crashes?

- It is a blocking protocol.

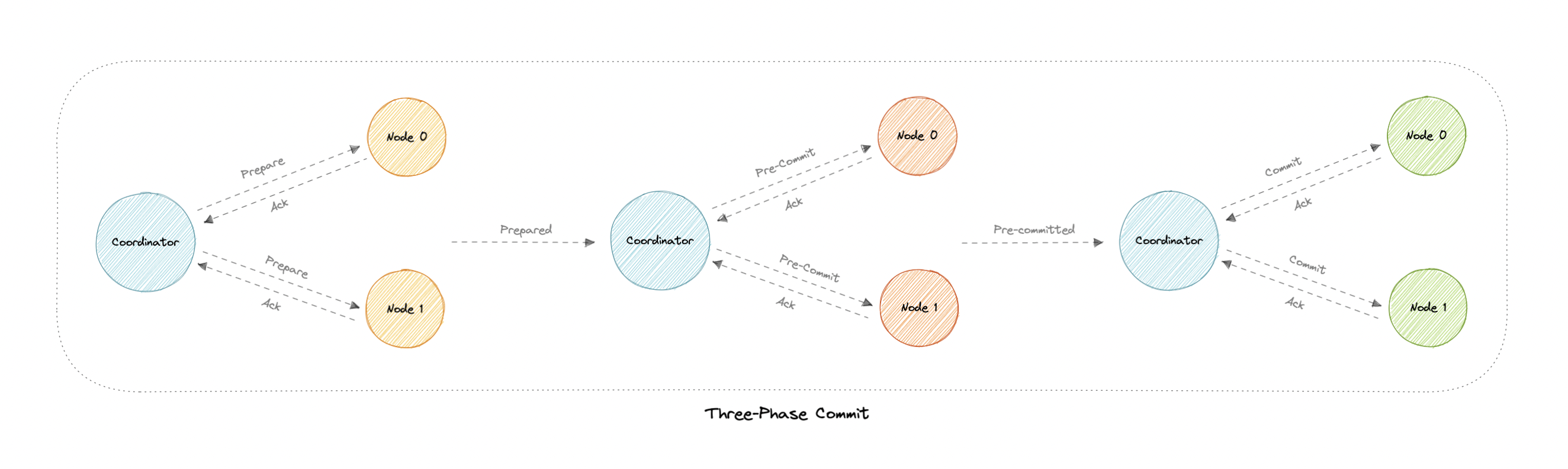

Three-phase commit

Three-phase commit (3PC) is an extension of the two-phase commit where the commit phase is split into two phases. This helps with the blocking problem that occurs in the two-phase commit protocol.

Phases

Three-phase commit consists of the following phases:

Prepare phase

This phase is the same as the two-phase commit.

Pre-commit phase

Coordinator issues the pre-commit message and all the participating nodes must acknowledge it. If a participant fails to receive this message in time, then the transaction is aborted.

Commit phase

This step is also similar to the two-phase commit protocol.

Why is the Pre-commit phase helpful?

The pre-commit phase accomplishes the following:

- If the participant nodes are found in this phase, that means that every participant has completed the first phase. The completion of prepare phase is guaranteed.

- Every phase can now time out and avoid indefinite waits.

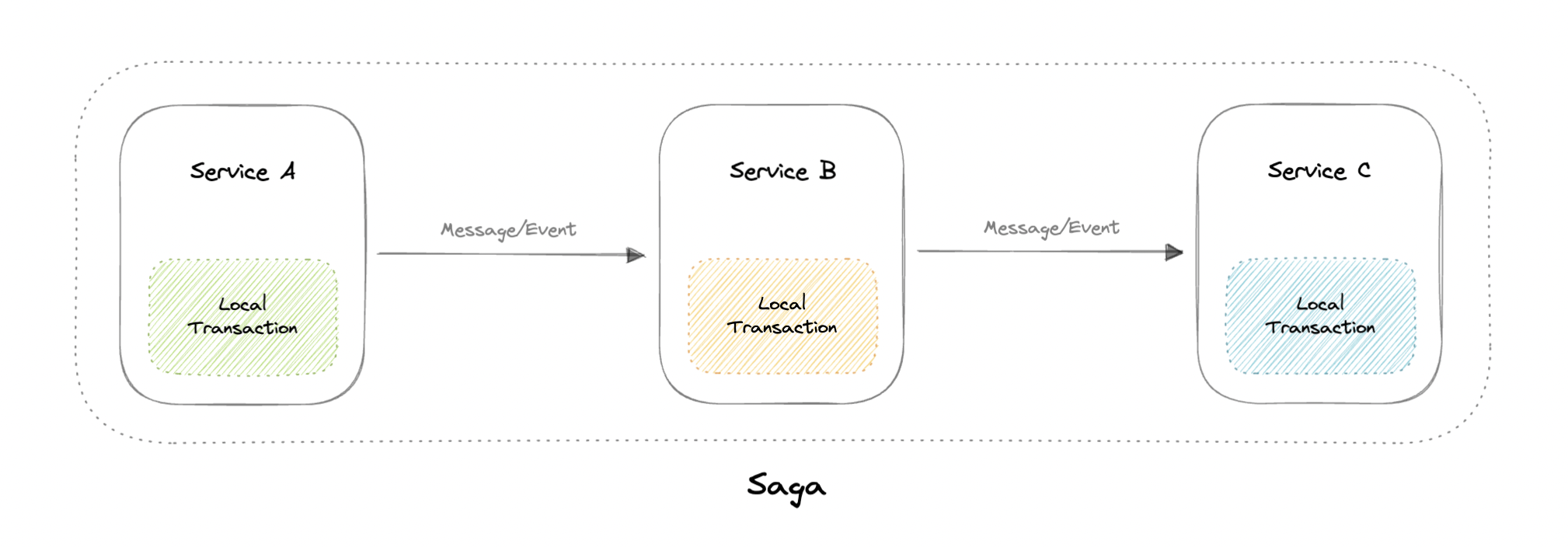

Sagas

A saga is a sequence of local transactions. Each local transaction updates the database and publishes a message or event to trigger the next local transaction in the saga. If a local transaction fails because it violates a business rule then the saga executes a series of compensating transactions that undo the changes that were made by the preceding local transactions.

Coordination

There are two common implementation approaches:

- Choreography: Each local transaction publishes domain events that trigger local transactions in other services.

- Orchestration: An orchestrator tells the participants what local transactions to execute.

Problems

- The Saga pattern is particularly hard to debug.

- There’s a risk of cyclic dependency between saga participants.

- Lack of participant data isolation imposes durability challenges.

- Testing is difficult because all services must be running to simulate a transaction.