ddd, hexagonal architecture, onion architecture, clean architecture, CQRS

This post is part of software architecture chronicles__, a series of posts about Software Architecture__. In them, I write about what I’ve learned about Software Architecture, how I think of it, and how I use that knowledge. The contents of this post might make more sense if you read the previous posts in this series.

After graduating from University I followed a career as a high school teacher until a few years ago I decided to drop it and become a full-time software developer.

From then on, I have always felt like I need to recover the “lost” time and learn as much as possible, as fast as possible. So I have become a bit of an addict in experimenting, reading and writing, with a special focus on software design and architecture. That’s why I write these posts, to help me learn.

In my last posts, I’ve been writing about many of the concepts and principles that I’ve learned and a bit about how I reason about them. But I see these as just pieces of big a puzzle.

Today’s post is about how I fit all of these pieces together and, as it seems I should give it a name, I call it Explicit Architecture. Furthermore, these concepts have all “passed their battle trials” and are used in production code on highly demanding platforms. One is a SaaS e-com platform with thousands of web-shops worldwide, another one is a marketplace, live in 2 countries with a message bus that handles over 20 million messages per month.

Fundamental blocks of the system

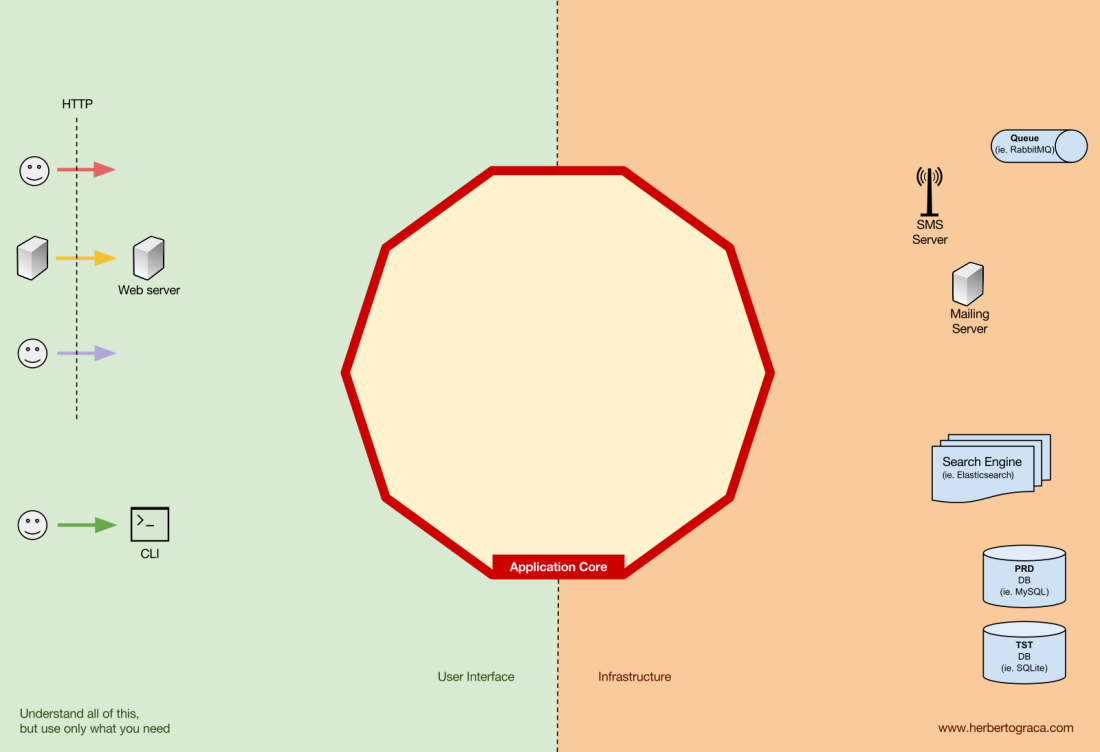

I start by recalling EBI and Ports & Adapters architectures. Both of them make an explicit separation of what code is internal to the application, what is external, and what is used for connecting internal and external code.

Furthermore, Ports & Adapters architecture explicitly identifies three fundamental blocks of code in a system:

- What makes it possible to run a user interface, whatever type of user interface it might be;

- The system business logic, or application core, which is used by the user interface to actually make things happen;

- Infrastructure code, that connects our application core to tools like a database, a search engine or 3rd party APIs.

The application core is what we should really care about. It is the code that allows our code to do what it is supposed to do, it IS our application. It might use several user interfaces (progressive web app, mobile, CLI, API, …) but the code actually doing the work is the same and is located in the application core, it shouldn’t really matter what UI triggers it.

As you can imagine, the typical application flow goes from the code in the user interface, through the application core to the infrastructure code, back to the application core and finally deliver a response to the user interface.

Tools

Far away from the most important code in our system, the application core, we have the tools that our application uses, for example, a database engine, a search engine, a Web server or a CLI console (although the last two are also delivery mechanisms).

While it might feel weird to put a CLI console in the same “bucket” as a database engine, and although they have different types of purposes, they are in fact tools used by the application. The key difference is that, while the CLI console and the web server are used to tell our application to do something, the database engine is told by our application to do something. This is a very relevant distinction, as it has strong implications on how we build the code that connects those tools with the application core.

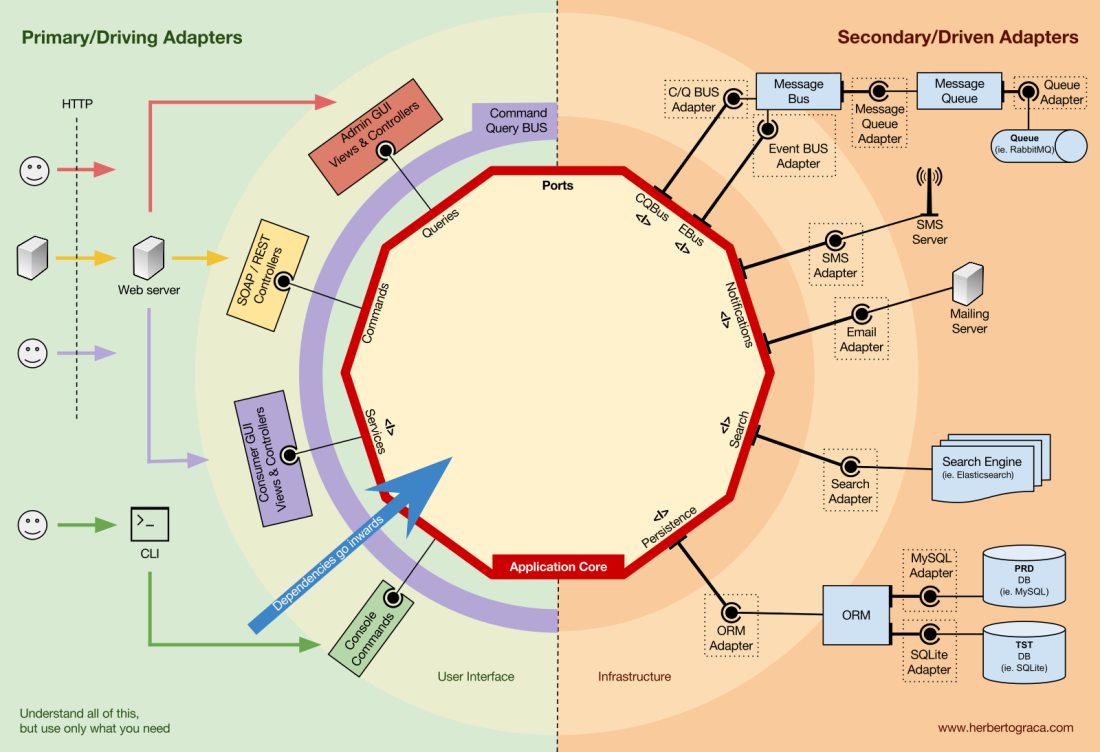

Connecting the tools and delivery mechanisms to the Application Core

The code units that connect the tools to the application core are called adapters (Ports & Adapters Architecture). The adapters are the ones that effectively implement the code that will allow the business logic to communicate with a specific tool and vice-versa.

The adapters that tell our application to do something are called Primary or Driving Adapters while the ones that are told by our application to do something are called Secondary or Driven Adapters.

Ports

These Adapters, however, are not randomly created. They are created to fit a very specific entry point to the Application Core, a Port. A port is nothing more than a specification of how the tool can use the application core, or how it is used by the Application Core. In most languages and in its most simple form, this specification, the Port, will be an Interface, but it might actually be composed of several Interfaces and DTOs.

It’s important to note that the Ports (Interfaces) belong inside the business logic, while the adapters belong outside. For this pattern to work as it should, it is of utmost importance that the Ports are created to fit the Application Core needs and not simply mimic the tools APIs.

Primary or Driving Adapters

The Primary or Driver Adapters wrap around a Port and use it to tell the Application Core what to do. They translate whatever comes from a delivery mechanism into a method call in the Application Core.

In other words, our Driving Adapters are Controllers or Console Commands who are injected in their constructor with some object whose class implements the interface (Port) that the controller or console command requires.

In a more concrete example, a Port can be a Service interface or a Repository interface that a controller requires. The concrete implementation of the Service, Repository or Query is then injected and used in the Controller.

Alternatively, a Port can be a Command Bus or Query Bus interface. In this case, a concrete implementation of the Command or Query Bus is injected into the Controller, who then constructs a Command or Query and passes it to the relevant Bus.

Secondary or Driven Adapters

Unlike the Driver Adapters, who wrap around a port, the Driven Adapters implement a Port, an interface, and are then injected into the Application Core, wherever the port is required (type-hinted).

For example, let’s suppose that we have a naive application which needs to persist data. So we create a persistence interface that meets its needs, with a method to save an array of data and a method to delete a line in a table by its ID. From then on, wherever our application needs to save or delete data we will require in its constructor an object that implements the persistence interface that we defined.

Now we create an adapter specific to MySQL which will implement that interface. It will have the methods to save an array and delete a line in a table, and we will inject it wherever the persistence interface is required.

If at some point we decide to change the database vendor, let’s say to PostgreSQL or MongoDB, we just need to create a new adapter that implements the persistence interface and is specific to PostgreSQL, and inject the new adapter instead of the old one.

Inversion of control

A characteristic to note about this pattern is that the adapters depend on a specific tool and a specific port (by implementing an interface). But our business logic only depends on the port (interface), which is designed to fit the business logic needs, so it doesn’t depend on a specific adapter or tool.

This means the direction of dependencies is towards the centre, it’s the inversion of control principle at the architectural level.

Although, again, it is of utmost importance that the Ports are created to fit the Application Core needs and not simply mimic the tools APIs.

Application Core organisation

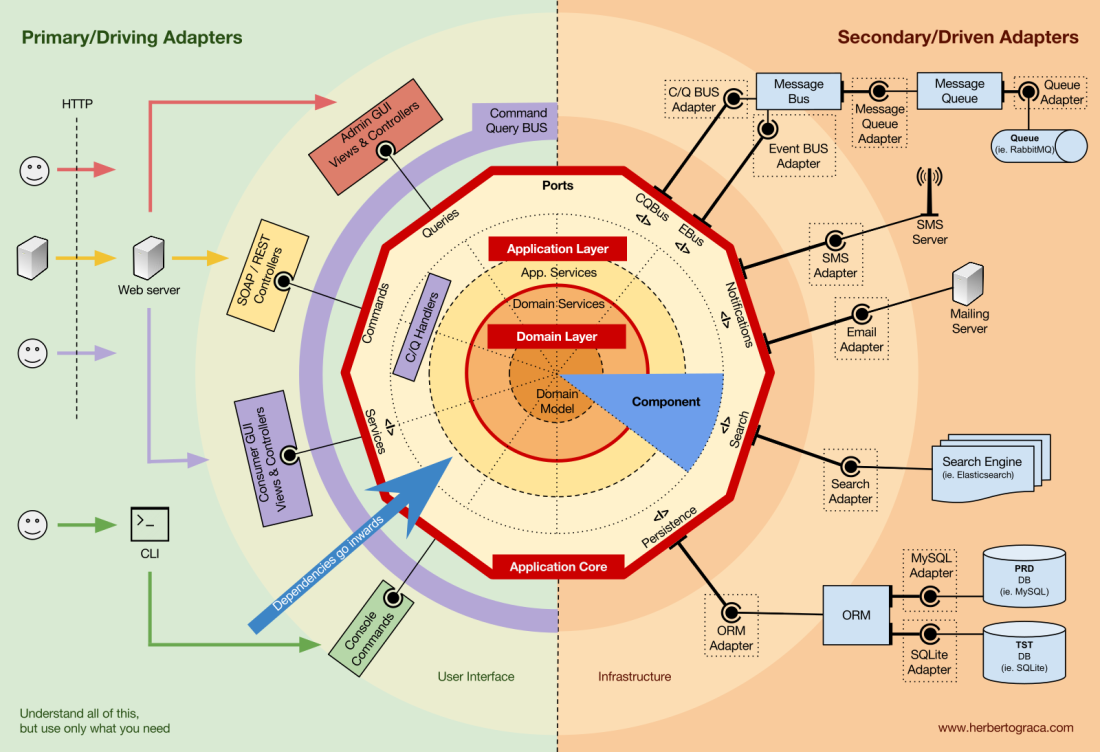

The Onion Architecture picks up the DDD layers and incorporates them into the Ports & Adapters Architecture. Those layers are intended to bring some organisation to the business logic, the interior of the Ports & Adapters “hexagon”, and just like in Ports & Adapters, the dependencies direction is towards the centre.

Application Layer

The use cases are the processes that can be triggered in our Application Core by one or several User Interfaces in our application. For example, in a CMS we could have the actual application UI used by the common users, another independent UI for the CMS administrators, another CLI UI, and a web API. These UIs (applications) could trigger use cases that can be specific to one of them or reused by several of them.

The use cases are defined in the Application Layer, the first layer provided by DDD and used by the Onion Architecture.

This layer contains Application Services (and their interfaces) as first class citizens, but it also contains the Ports & Adapters interfaces (ports) which include ORM interfaces, search engines interfaces, messaging interfaces and so on. In the case where we are using a Command Bus and/or a Query Bus, this layer is where the respective Handlers for the Commands and Queries belong.

The Application Services and/or Command Handlers contain the logic to unfold a use case, a business process. Typically, their role is to:

- use a repository to find one or several entities;

- tell those entities to do some domain logic;

- and use the repository to persist the entities again, effectively saving the data changes.

The Command Handlers can be used in two different ways:

- They can contain the actual logic to perform the use case;

- They can be used as mere wiring pieces in our architecture, receiving a Command and simply triggering logic that exists in an Application Service.

Which approach to use depends on the context, for example:

- Do we already have the Application Services in place and are now adding a Command Bus?

- Does the Command Bus allow specifying any class/method as a handler, or do they need to extend or implement existing classes or interfaces?

This layer also contains the triggering of Application Events, which represent some outcome of a use case. These events trigger logic that is a side effect of a use case, like sending emails, notifying a 3rd party API, sending a push notification, or even starting another use case that belongs to a different component of the application.

Domain Layer

Further inwards, we have the Domain Layer. The objects in this layer contain the data and the logic to manipulate that data, that is specific to the Domain itself and it’s independent of the business processes that trigger that logic, they are independent and completely unaware of the Application Layer.

Domain Services

As I mentioned above, the role of an Application Service is to:

- use a repository to find one or several entities;

- tell those entities to do some domain logic;

- and use the repository to persist the entities again, effectively saving the data changes.

However, sometimes we encounter some domain logic that involves different entities, of the same type or not, and we feel that that domain logic does not belong in the entities themselves, we feel that that logic is not their direct responsibility.

So our first reaction might be to place that logic outside the entities, in an Application Service. However, this means that that domain logic will not be reusable in other use cases: domain logic should stay out of the application layer!

The solution is to create a Domain Service, which has the role of receiving a set of entities and performing some business logic on them. A Domain Service belongs to the Domain Layer, and therefore it knows nothing about the classes in the Application Layer, like the Application Services or the Repositories. In the other hand, it can use other Domain Services and, of course, the Domain Model objects.

Domain Model

In the very centre, depending on nothing outside it, is the Domain Model, which contains the business objects that represent something in the domain. Examples of these objects are, first of all, Entities but also Value Objects, Enums and any objects used in the Domain Model.

The Domain Model is also where Domain Events “live”. These events are triggered when a specific set of data changes and they carry those changes with them. In other words, when an entity changes, a Domain Event is triggered and it carries the changed properties new values. These events are perfect, for example, to be used in Event Sourcing.

Components

So far we have been segregating the code based on layers, but that is the fine-grained code segregation. The coarse-grained segregation of code is at least as important and it’s about segregating the code according to sub-domains and bounded contexts, following Robert C. Martin ideas expressed in screaming architecture. This is often referred to as “Package by feature” or “Package by component” as opposed to”Package by layer“, and it’s quite well explained by Simon Brown in his blog post “Package by component and architecturally-aligned testing“:

I am an advocate for the “Package by component” approach and, picking up on Simon Brown diagram about Package by component, I would shamelessly change it to the following:

These sections of code are cross-cutting to the layers previously described, they are the components of our application. Examples of components can be Authentication, Authorization, Billing, User, Review or Account, but they are always related to the domain. Bounded contexts like Authorization and/or Authentication should be seen as external tools for which we create an adapter and hide behind some kind of port.

Decoupling the components

Just like the fine-grained code units (classes, interfaces, traits, mixins, …), also the coarsely grained code-units (components) benefit from low coupling and high cohesion.

To decouple classes we make use of Dependency Injection, by injecting dependencies into a class as opposed to instantiating them inside the class, and Dependency Inversion, by making the class depend on abstractions (interfaces and/or abstract classes) instead of concrete classes. This means that the depending class has no knowledge about the concrete class that it is going to use, it has no reference to the fully qualified class name of the classes that it depends on.

In the same way, having completely decoupled components means that a component has no direct knowledge of any another component. In other words, it has no reference to any fine-grained code unit from another component, not even interfaces! This means that Dependency Injection and Dependency Inversion are not enough to decouple components, we will need some sort of architectural constructs. We might need events, a shared kernel, eventual consistency, and even a discovery service!

Triggering logic in other components

When one of our components (component B) needs to do something whenever something else happens in another component (component A), we can not simply make a direct call from component A to a class/method in component B because A would then be coupled to B.

However we can make A use an event dispatcher to dispatch an application event that will be delivered to any component listening to it, including B, and the event listener in B will trigger the desired action. This means that component A will depend on an event dispatcher, but it will be decoupled from B.

Nevertheless, if the event itself “lives” in A this means that B knows about the existence of A, it is coupled to A. To remove this dependency, we can create a library with a set of application core functionality that will be shared among all components, the Shared Kernel. This means that the components will both depend on the Shared Kernel but they will be decoupled from each other. The Shared Kernel will contain functionality like application and domain events, but it can also contain Specification objects, and whatever makes sense to share, keeping in mind that it should be as minimal as possible because any changes to the Shared Kernel will affect all components of the application. Furthermore, if we have a polyglot system, let’s say a micro-services ecosystem where they are written in different languages, the Shared Kernel needs to be language agnostic so that it can be understood by all components, whatever the language they have been written in. For example, instead of the Shared Kernel containing an Event class, it will contain the event description (ie. name, properties, maybe even methods although these would be more useful in a Specification object) in an agnostic language like JSON, so that all components/micro-services can interpret it and maybe even auto-generate their own concrete implementations. Read more about this in my followup post: More than concentric layers.

This approach works both in monolithic applications and distributed applications like micro-services ecosystems. However, when the events can only be delivered asynchronously, for contexts where triggering logic in other components needs to be done immediately this approach will not suffice! Component A will need to make a direct HTTP call to component B. In this case, to have the components decoupled, we will need a discovery service to which A will ask where it should send the request to trigger the desired action, or alternatively make the request to the discovery service who can proxy it to the relevant service and eventually return a response back to the requester. This approach will couple the components to the discovery service but will keep them decoupled from each other.

Getting data from other components

The way I see it, a component is not allowed to change data that it does not “own”, but it is fine for it to query and use any data.

Data storage shared between components

When a component needs to use data that belongs to another component, let’s say a billing component needs to use the client name which belongs to the accounts component, the billing component will contain a query object that will query the data storage for that data. This simply means that the billing component can know about any dataset, but it must use the data that it does not “own” as read-only, by the means of queries.

Data storage segregated per component

In this case, the same pattern applies, but we have more complexity at the data storage level. Having components with their own data storage means each data storage contains:

- A set of data that it owns and is the only one allowed to change, making it the single source of truth;

- A set of data that is a copy of other components data, which it can not change on its own, but is needed for the component functionality, and it needs to be updated whenever it changes in the owner component.

Each component will create a local copy of the data it needs from other components, to be used when needed. When the data changes in the component that owns it, that owner component will trigger a domain event carrying the data changes. The components holding a copy of that data will be listening to that domain event and will update their local copy accordingly.

Flow of control

As I said above, the flow of control goes, of course, from the user into the Application Core, over to the infrastructure tools, back to the Application Core and finally back to the user. But how exactly do classes fit together? Which ones depend on which ones? How do we compose them?

Following Uncle Bob, in his article about Clean Architecture, I will try to explain the flow of control with UMLish diagrams…

Without a Command/Query Bus

In the case we do not use a command bus, the Controllers will depend either on an Application Service or on a Query object.

[EDIT – 2017-11-18] I completely missed the DTO I use to return data from the query, so I added it now. Tkx to MorphineAdministered who pointed it out for me.

In the diagram above we use an interface for the Application Service, although we might argue that it is not really needed since the Application Service is part of our application code and we will not want to swap it for another implementation, although we might refactor it entirely.

The Query object will contain an optimized query that will simply return some raw data to be shown to the user. That data will be returned in a DTO which will be injected into a ViewModel. ThisViewModel may have some view logic in it, and it will be used to populate a View.

The Application Service, on the other hand, will contain the use case logic, the logic we will trigger when we want to do something in the system, as opposed to simply view some data. The Application Services depend on Repositories which will return the Entity(ies) that contain the logic which needs to be triggered. It might also depend on a Domain Service to coordinate a domain process in several entities, but that is hardly ever the case.

After unfolding the use case, the Application Service might want to notify the whole system that that use case has happened, in which case it will also depend on an event dispatcher to trigger the event.

It is interesting to note that we place interfaces both on the persistence engine and on the repositories. Although it might seem redundant, they serve different purposes:

- The persistence interface is an abstraction layer over the ORM so we can swap the ORM being used with no changes to the Application Core.

- The repository interface is an abstraction on the persistence engine itself. Let’s say we want to switch from MySQL to MongoDB. The persistence interface can be the same, and, if we want to continue using the same ORM, even the persistence adapter will stay the same. However, the query language is completely different, so we can create new repositories which use the same persistence mechanism, implement the same repository interfaces but builds the queries using the MongoDB query language instead of SQL.

With a Command/Query Bus

In the case that our application uses a Command/Query Bus, the diagram stays pretty much the same, with the exception that the controller now depends on the Bus and on a command or a Query. It will instantiate the Command or the Query, and pass it along to the Bus who will find the appropriate handler to receive and handle the command.

In the diagram below, the Command Handler then uses an Application Service. However, that is not always needed, in fact in most of the cases the handler will contain all the logic of the use case. We only need to extract logic from the handler into a separated Application Service if we need to reuse that same logic in another handler.

[EDIT – 2017-11-18] I completely missed the DTO I use to return data from the query, so I added it now. Tkx to MorphineAdministered who pointed it out for me.

You might have noticed that there is no dependency between the Bus and the Command, the Query nor the Handlers. This is because they should, in fact, be unaware of each other in order to provide for good decoupling. The way the Bus will know what Handler should handle what Command, or Query, should be set up with mere configuration.

As you can see, in both cases all the arrows, the dependencies, that cross the border of the application core, they point inwards. As explained before, this a fundamental rule of Ports & Adapters Architecture, Onion Architecture and Clean Architecture.

Conclusion

The goal, as always, is to have a codebase that is loosely coupled and high cohesive, so that changes are easy, fast and safe to make.

Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.

Eisenhower

This infographic is a concept map. Knowing and understanding all of these concepts will help us plan for a healthy architecture, a healthy application.

Nevertheless:

The map is not the territory.

Alfred Korzybski

Meaning that these are just guidelines! The application is the territory, the reality, the concrete use case where we need to apply our knowledge, and that is what will define what the actual architecture will look like!

We need to understand all these patterns, but we also always need to think and understand exactly what our application needs, how far should we go for the sake of decoupling and cohesiveness. This decision can depend on plenty of factors, starting with the project functional requirements, but can also include factors like the time-frame to build the application, the lifespan of the application, the experience of the development team, and so on.

This is it, this is how I make sense of it all. This is how I rationalize it in my head.

I expanded these ideas a bit more on a followup post: More than concentric layers.

However, how do we make all this explicit in the code base? That’s the subject of one of my next posts: how to reflect the architecture and domain, in the code.

Last but not least, thanks to my colleague Francesco Mastrogiacomo, for helping me make my infographic look nice.