7 Cognitive Biases Silently Sabotaging Your Career

People often ask why I stayed at Amazon for 18 years. “Isn’t it brutal there?” “How did you survive the pressure cooker for so long?”

My experience doesn’t match the horror stories. For me, Amazon was challenging but fair - a place where I thrived and grew from support engineer to principal software engineer.

Over time, I realized that my positive experience might be survivorship bias in action.

What Are Cognitive Biases?

Cognitive biases are errors in thinking that affect our decisions. Think of them as shortcuts our brains take. They are usually helpful, sometimes harmful, and almost always invisible to us.

That’s what makes them dangerous. You can’t fix what you don’t know exists.

They are so clear when we watch others because we have perspective they don’t.

But don’t trick yourself into thinking you don’t have biases. You most certainly do.

This week, I’ll walk through 7 cognitive biases that might be silently shaping your career or worse, holding you back.

1. Survivorship Bias: Learning Only From Winners

What it is: Focusing only on people or things that “survived” a selection process while ignoring those that didn’t, leading to false conclusions about what drives success.

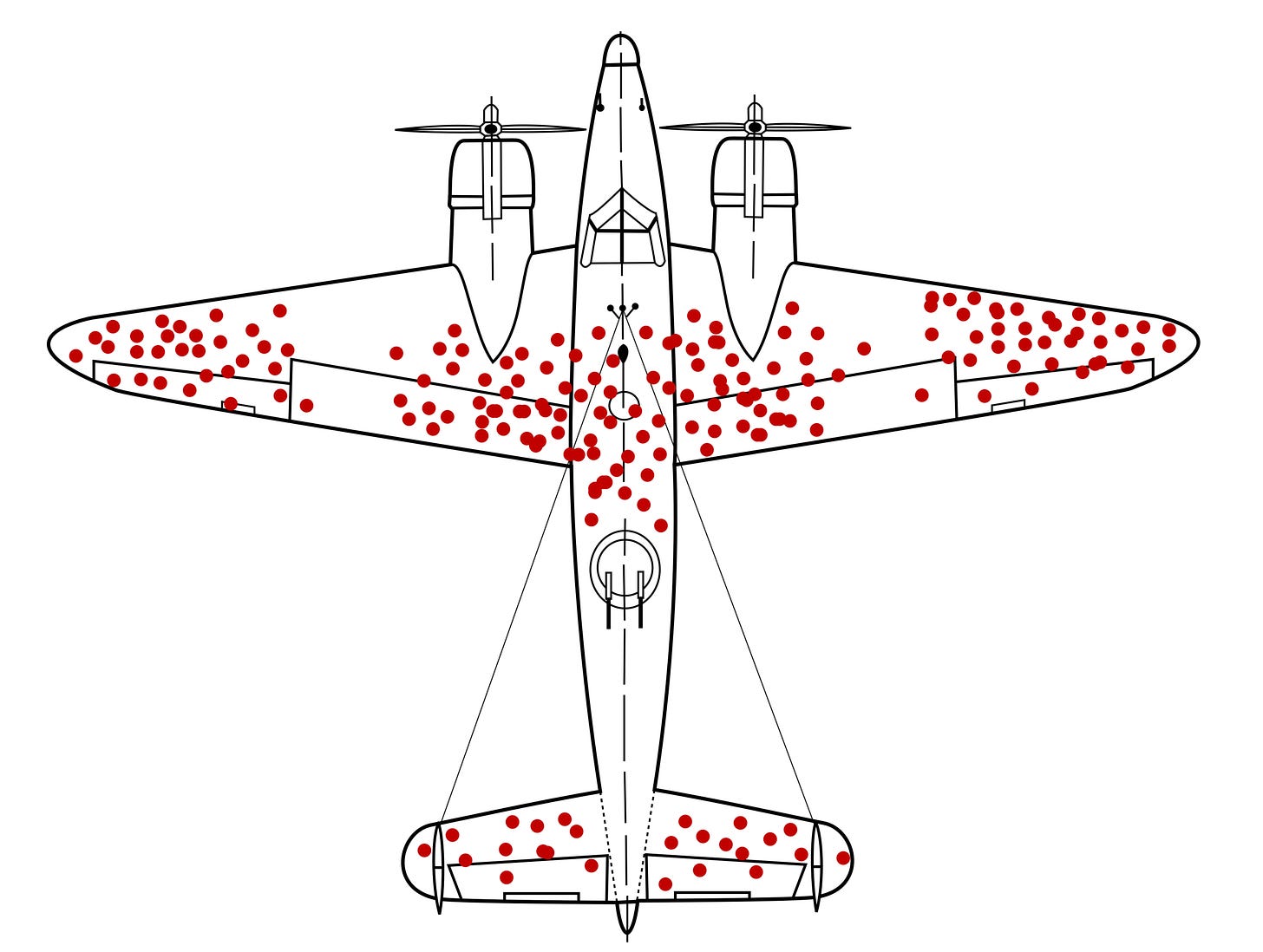

The classic example: During World War II, statisticians analyzed damage on returning aircraft to decide where to add armor. Their first instinct was to reinforce the areas showing the most damage. But mathematician Abraham Wald pointed out a critical flaw: they were only seeing planes that survived being shot. The planes that didn’t return were likely hit in areas without visible damage on the survivors.

The key insight? Add armor to the areas showing no damage on returning planes - those were likely the critical areas where hits were fatal.

Here are places where returning planes suffered damage. The critical insight was to put armor where the bullets weren’t as they indicated places where damage was catastrophic.

Career example: When we look at successful people, we often focus only on their habits and traits. “Steve Jobs was confrontational and it worked for him” or “Elon Musk sleeps at the office” become templates we think we should follow.

But this ignores thousands who failed despite similar approaches. For every successful confrontational leader, there are dozens whose careers stalled because their style created enemies. For every workaholic who succeeded, many others burned out without achieving their goals.

Even my Amazon story suffers from this bias. You hear from me, someone who thrived there for 18 years. You have probably also heard from those who left after 6 months or 2 years because the culture wasn’t right for them. Their experiences are equally valid for understanding what it’s truly like to work there.

How to avoid it:

- Seek out stories of failure, not just success

- When analyzing successful strategies, also study those who used similar approaches but failed

- Remember that visible survivors represent only part of the story

- Ask “what am I not seeing?” when drawing conclusions from available data

- Consider selection effects in any population you’re studying

The next time someone tells you “successful people wake up at 5 AM,” ask yourself: How many unsuccessful people also wake up at 5 AM? And how many successful people sleep until 9?

2. Confirmation Bias: Seeing What You Want to See

What it is: Our brain’s tendency to notice, favor, and remember information that confirms our existing beliefs while ignoring evidence that contradicts them. It’s like wearing glasses that only let you see what you already think is true.

The science behind it: This bias is deeply rooted in how our brains process information. We naturally seek consistency in our beliefs to avoid the discomfort of cognitive dissonance - that uncomfortable feeling when we hold two conflicting thoughts. Our brains literally process contradictory information differently when it challenges our existing views.

A study during the 2004 presidential election placed partisan voters in MRI machines while they read contradictory statements from both candidates. The results were striking: voters not only easily spotted contradictions from the candidate they opposed but struggled to see the same logical flaws in their preferred candidate. Even more revealing, their brains processed the contradictions differently depending on who said them.

I have a sneaking suspicion that we’d get similar results in today’s political climate.

Career example: Early in my Amazon career, I was convinced that technical expertise was the only real path to advancement. I’d try to emulate every technically brilliant senior engineer while completely overlooking those who advanced through leadership skills, complementary product/business acumen, or strategic thinking.

For years, I focused solely on deepening my technical skills while ignoring feedback about my communication style and leadership approach. When passed over for promotion, I’d blame it on “politics” rather than recognizing the genuine gaps in my skill set that didn’t fit my self-image.

I was stuck in a loop: believe technical skills are all that matters → notice only technical superstars → conclude technical skills are all that matters.

How it hurts your career:

- You miss critical feedback that doesn’t align with your self-image

- You develop lopsided skills because you only invest in areas you already value

- You make the same mistakes repeatedly because you filter out evidence they’re problems

- You surround yourself with people who think like you, creating an echo chamber

- You dismiss valid alternative perspectives as wrong or irrelevant

How to overcome it:

- Actively seek contradictory evidence - Force yourself to ask, “What if I’m wrong about this?”

- Create a decision journal - Document your thought process and review it later to spot patterns

- Invite devil’s advocates - Find trusted colleagues who will challenge your thinking

- Diversify your information sources - Read perspectives from people with different backgrounds and beliefs

- Practice the steel man technique - Instead of dismantling the weakest version of opposing arguments (strawman), build and engage with the strongest possible version of views you disagree with

Quick win: Before your next important decision, write down not just the reasons supporting your preferred option, but force yourself to list at least five strong reasons why the alternative might be better. Show both lists to someone whose judgment you trust.

3. Sunk Cost Fallacy: Sticking With Bad Decisions

What it is: The tendency to continue with something because you’ve already invested resources in it (time, money, effort), even when cutting your losses would clearly be more beneficial. This bias makes past investments feel like they’ll be “wasted” if you don’t continue, even when continuing is worse than stopping.

The psychology behind it: Our brains hate feeling like we’ve lost something for nothing. The sunk cost fallacy is closely tied to loss aversion - our tendency to prefer avoiding losses over acquiring equivalent gains. Research shows we feel the pain of losses roughly twice as strongly as the pleasure of equivalent gains. This creates a powerful force keeping us committed to failing paths.

Studies show this bias appears across cultures and even in animals, suggesting it may be hardwired into our decision-making systems. It shows up in everything from finishing a bad movie (“I’ve already watched an hour!”) to continuing failed government projects that have already consumed billions.

Career example: One of my biggest career mistakes at Amazon was staying on a team for nearly five years despite clear signs it wasn’t serving my growth. The team had poor management and was working in a business segment that was clearly shrinking.

Every year I’d think about transferring, but each time I’d tell myself, “I’ve already invested so much time understanding this domain and these systems. If I leave now, all that specialized knowledge goes to waste.”

The truth was that each additional year was the real waste. My peers who made the hard decision to start fresh on growing teams with better leadership progressed much faster in their careers. By the time I finally transferred, I had to work twice as hard to catch up to where I could have been.

How it hurts your career:

- You remain in unfulfilling roles or companies long after they stop serving you

- You continue pursuing degrees or certifications that no longer align with your goals

- You keep pushing doomed projects rather than pivoting to more promising opportunities

- You maintain toxic relationships with colleagues or managers out of familiarity

- You refuse to abandon approaches that aren’t working because “you’ve put in so much already”

How to overcome it:

- Adopt a fresh start mindset - Regularly evaluate decisions as if you were starting from scratch today

- Focus on opportunity costs - Ask “What am I giving up by continuing this path?”

- Set clear exit criteria in advance - Define specific conditions that will trigger a change of course

- Celebrate smart abandonments - Recognize and reward the courage to cut losses when appropriate

- Use the 10/10/10 rule - Ask how a decision will impact you in 10 minutes, 10 months, and 10 years

Quick win: Identify one ongoing commitment that’s draining your energy. Ask yourself: “If I weren’t already involved in this, would I choose to start it today?” If the answer is no, create an exit plan this week.

4. The Dunning-Kruger Effect: Not Knowing What You Don’t Know

What it is: A bias where people with limited knowledge or competence in a specific domain grossly overestimate their abilities. The less you know about something, the more likely you are to be overconfident about your understanding of it.

The science behind it: Named after psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger, their research showed that the least competent performers in various domains consistently rated their abilities far higher than their actual performance warranted. Even more fascinating, as people gained genuine expertise, their self-assessment often became more modest.

The effect creates a double burden: not only do people perform poorly due to their lack of skill, but that same lack of skill prevents them from recognizing their own incompetence. You literally don’t know enough to know how much you don’t know.

Career example: As a new senior engineer at Amazon, I was brimming with confidence about my ability to manage projects. I’d been a strong mid-level contributor and assumed leadership would come naturally. Six months in, my first real feedback session was a wake-up call.

My team found me micromanaging, unclear in my expectations, and playing favorites without realizing it. While I thought I was excelling, I was actually creating confusion and resentment. My confidence had masked my incompetence. Only after recognizing how much I didn’t know about leadership could I begin to improve.

How it hurts your career:

- You attempt tasks too far beyond your actual skill level and fail publicly

- You dismiss learning opportunities because you think you already know enough

- You give poor advice with unwarranted confidence

- You miss signals that you’re underperforming

- You avoid asking questions that would reveal your knowledge gaps

How to overcome it:

- Assume you have blind spots - Approach new skills with genuine humility

- Test your knowledge - Look for objective ways to measure your abilities

- Seek regular, candid feedback - Ask specific questions that can reveal gaps

- Learn from true experts - Observe how much nuance and complexity they see

- Cultivate a beginner’s mindset - Value curiosity over certainty

Quick win: Identify a skill where you consider yourself above average. Find someone with undeniable expertise in that area and ask them to evaluate your abilities. Their assessment might surprise you.

5. Fundamental Attribution Error: Judging Others Too Harshly

What it is: Our tendency to attribute other people’s behaviors to their character or personality while explaining our own behaviors through situational factors. When others fail, it’s because of who they are; when we fail, it’s because of circumstances.

The psychology behind it: This bias stems from our limited perspective - we have complete access to all the situational factors affecting our own behavior, but only see others’ external actions. Research shows this bias is particularly strong in individualistic cultures that emphasize personal traits over contextual factors.

Studies show how pervasive this bias is: we consistently overestimate the role of personality and underestimate the power of the situation when explaining others’ actions, even when we have clear evidence of situational constraints.

Career example: I once had a team member who consistently missed deadlines. In my mind, I labeled him as “unreliable,” “lazy,” and “lacking commitment.” When I missed deadlines myself, I immediately pointed to the complexity of the task, unexpected obstacles, or competing priorities.

Later I discovered he was supporting a family member through a serious illness - something he hadn’t shared because he worried about being seen as making excuses. His circumstances, not his character, explained his performance. This realization fundamentally changed how I approach performance issues to this day.

How it hurts your career:

- You make unfair judgments about colleagues that damage working relationships

- You miss opportunities to solve systemic problems by focusing on “problem people”

- You create toxic workplace cultures by assuming bad intentions

- You fail to understand the real constraints affecting your team’s performance

- You dismiss valuable contributors based on superficial assessments

How to overcome it:

- Practice empathy by default - Assume good intentions until proven otherwise

- Consider situational factors first - Ask “What might explain this behavior?”

- Apply the same standards to yourself and others

- Recognize the limits of your perspective - You never have the full context of someone else’s actions

- Seek understanding before judgment - Ask questions rather than making assumptions

Quick win: The next time a colleague disappoints you, write down three possible situational explanations for their behavior before allowing yourself to make any character judgments.

6. Optimism Bias: Overestimating Success

What it is: Our tendency to believe we are less likely to experience negative events and more likely to experience positive outcomes than is statistically probable. It’s our brain’s built-in rose-colored glasses that distort risk assessment and planning.

The science behind it: Brain scans have actually identified regions in our brains that appear to be responsible for this bias. When we imagine positive future events, our brains show increased activity compared to when we imagine negative events. This bias persists even when we’re explicitly warned about it - we acknowledge it exists but still believe we’re the exception.

Research shows this bias is nearly universal across cultures and ages, suggesting it might have evolutionary advantages despite its potential downsides. It helps explain everything from entrepreneurial risk-taking to why we consistently underestimate project timelines.

Career example: Almost every project plan I encountered at Amazon suffered from this bias. Teams would present timelines that assumed everything would go perfectly - no unexpected technical challenges, no team members getting sick, no dependencies falling through, no competing priorities emerging.

I eventually learned to automatically add 50% to any timeline estimate, not because my teams were dishonest, but because humans are fundamentally wired to underestimate difficulties and overestimate their ability to overcome them. Once I adjusted for this bias systematically, our delivery predictability dramatically improved (but things still took longer than we expected).

How it hurts your career:

- You consistently miss deadlines because you underestimate task complexity

- You take on more work than you can realistically handle

- You underestimate risks when making major career decisions

- You fail to build in contingency plans for likely obstacles

- You set unrealistic expectations that damage your credibility when unmet

How to overcome it:

- Use pre-mortems - Imagine your project has failed and work backward to identify causes

- Reference class forecasting - Look at outcomes of similar past situations, not just your specific case

- Build in buffer time - Systematically add contingency to estimates (I used to use 50%, most people suggest adding 100%)

- Consider the worst-case scenario - Explicitly plan for what could go wrong

- Seek external perspectives - Others can often see your blind spots more clearly

Quick win: For your next important deadline, double the time you think it will take, then commit to a timeline somewhere between your original estimate and this doubled figure.

7. Authority Bias: Trusting Experts Too Much

What it is: Our tendency to give greater weight to the opinions of authority figures and be influenced by their views, regardless of their actual expertise on the specific topic at hand.

The psychology behind it: This bias has deep evolutionary roots - deferring to authority likely helped our ancestors survive. Most famously demonstrated in Milgram’s obedience experiments, this bias shows how readily we can surrender our judgment to perceived authorities.

Studies show we process information differently when it comes from a perceived authority figure - we scrutinize it less carefully and recall it more readily. The effect is amplified by symbols of authority like titles, uniforms, or credentials, even when they’re not relevant to the domain in question.

Career example: In one critical architectural review at Amazon, a principal engineer (later distinguished engineer) suggested an approach that felt fundamentally flawed. Despite my reservations, I deferred to his authority and expertise. Six months and thousands of engineering hours later, we had to revert to something closer to my original instinct.

What I failed to recognize was that while he had greater general expertise, I had deeper context on this specific problem. His seniority had effectively silenced my contextual knowledge, leading to a costly detour.

I learned that even the most brilliant people don’t have full visibility, and sometimes a less experienced person with deeper context can have better insights on a specific problem.

How it hurts your career:

- You implement approaches you don’t believe in just because they came from authority

- You fail to contribute valuable insights when they contradict senior opinions

- You miss opportunities to learn from those with less formal authority but more relevant expertise

- You allow hierarchical structures to override better judgment

- You abdicate responsibility for decisions by deferring to others

How to overcome it:

- Evaluate ideas on their merits, not on who proposed them

- Question credentials - Ask if the authority’s expertise is truly relevant to this specific domain

- Create psychological safety - Establish environments where junior team members feel safe challenging senior ones

- Practice intellectual autonomy - Take responsibility for your own conclusions

- Use structured decision processes that evaluate evidence systematically

Quick win: The next time you’re in a meeting with senior leaders, commit to asking at least one thoughtful question that gently challenges an assumption. Frame it as seeking understanding rather than confrontation.

Seeing Your Blind Spots

The hardest thing about biases is that they’re invisible when you’re in their grip. They form your reality, not just your view of it.

So how do you see what you can’t see?

- Build a diverse network - Surrounding yourself with people who think differently increases the chances someone will spot what you miss.

- Institutionalize devil’s advocacy - Assign someone to argue against the prevailing view in important decisions.

- Journal your decisions - Record not just what you decided but why, then review later to see patterns in your thinking.

- Seek feedback relentlessly - Create safe spaces for others to tell you what you might be missing.

- Study your mistakes - When things don’t go as expected, ask “What bias might have influenced my thinking here?”

The journey from good to great is about unlearning the mental shortcuts that limit your perspective.

What biases have you noticed affecting your career decisions? Share in the comments - your blind spot might be someone else’s moment of clarity.